Canvas course checklist

Canvas course checklist

Essential tasks for each phase of the term

From basic Canvas settings to content organization to administrative tasks, this Canvas and course checklist outlines essential course tasks for every term at Portland State. This checklist is also available as an interactive Google doc. Make your own copy of the checklist for each of your course reviews!

Before the term: Course prep checklist

Suggested timeline: At least 2 weeks before the term starts

- Add a syllabus that outlines your course expectations and is accessible and culturally inclusive.

- Use Canvas modules to organize content by week or topic. Give each module and item a descriptive title to support navigation and accessibility.

- Publish all course items so students can access them. This includes all pages and links in your modules as well as assignments, quizzes, and discussions.

- Check that all your course materials are accessible. Use the Canvas Accessibility Checker to check materials created in the Canvas Rich Content Editor.

- If you created videos, make sure your videos are properly captioned.

- Use the Canvas Course Link Validator to identify broken links in your course.

- Use Student View to preview your course from a student's perspective.

- Log in to your course through the mobile app to review the mobile experience. More than half of PSU students use the Canvas mobile app.

- Review your discussions, if used. Verify that they:

- Correct due date dates

- Clear instructions with examples and a rubric, if possible

- Correct grade settings, if graded

- Group/peer review settings, if applicable

- Review your assignments, if used. Verify that they have:

- Correct dates

- Clear instructions with examples and a rubric, if possible

- Correct grade settings, if graded

- Group or peer review settings, if used

- Review your quizzes, if used. Verify that they have:

- Accurate availability and due dates

- Clear instructions with examples and a rubric, if possible

- Correct grade settings, if graded

- Review your gradebook. Check that Gradebook reflects your grading policy and is aligned with the syllabus.

- Verify that the calendar tool accurately reflects all assignment due dates and other events.

- Customize your Canvas dashboard to show only the courses you want to display.

- Customize your Course navigation menu to include only relevant tools and hide unused items.

- Upload a course image for your Canvas Dashboard card..

- Update your Canvas profile, including name, profile picture, pronouns (if comfortable), and preferred contact methods. Students in all your courses can read your profile. (You only need to do this once!)

- Review the default Canvas notification settings and adjust them as preferred.

- Publish your Canvas course shell when you're ready. (By default, students can only access it after it's published and the start date has passed.)

- Tip: If you want students to access the course early, adjust the course start date in Settings.

- Make sure your Zoom application is up to date. If you schedule Zoom meetings through Google Calendar using a browser plugin, make sure the plugin is also up to date.

- Reinstall the newest version of Chrome or Firefox.

- Log in to MediaSpace. If you’ve never used your Media Space account, be sure to log in at least once. This allows automatic copies of your Zoom meetings to be stored there. (Note: You do not need to do this each term -- just once during your time at PSU.)

- Schedule your meetings from within Canvas if you’re using Zoom for class. This will create Zoom meeting links for your course that students can access directly in Canvas.

- Schedule an office hour on Zoom before the term begins. A brief check-in can reduce student anxiety and boost early engagement.

- Send a welcome email to your class using Google Groups. Here are sample email templates to help you get started. Let students know:

- When they can access the course in Canvas

- How to get started

- Where to ask questions

During the term: Checklist for engagement

The first few weeks of the term are your chance to set the tone, build community, and help students feel connected to you and each other.

In all course formats:

- Manage your waitlist. On the first day of the term, the automated waitlist function will stop. You’ll need to manually manage enrollment in Banweb by issuing registration overrides. (Learn more about waitlists.)

- Track student attendance. The Department of Education requires instructors to document attendance for each course. Learn more in the Faculty Guide to Initiation of Attendance.

If you're teaching online:

- Introduce yourself. Introductions can help establish a social presence — that someone is real and available. A video is a great way to do this, but even an image and a brief message can help students learn more about you.

- Ask your students to introduce themselves. Invite students to share a bit about who they are. This supports community-building, open communication, and regular interaction throughout the course.

- Record an orientation video. Create a short video overview of your course, including the syllabus, learning objectives, required materials, expectations for interaction, and key due dates.

Staying present in your course is key to student engagement and success. Here are some ways to stay connected:

- Do a midterm check-in. Use a quick Google Form survey to gather student feedback on what’s working and what could be improved. Two simple, effective questions:

- What is one thing your instructor could change to improve your learning in this course?

- What is one thing YOU could change to improve your learning in this course?

- Offer an optional office hour. Holding office hours—in person or via Zoom—can help build rapport and increase engagement. Plan an interactive element to encourage participation.

End of term: Checklist for course conclusion

As the term ends, here are a few things to do before you relax and celebrate your course success! This checklist outlines how to share grades with both your students and the registrar, and how to prepare for the next time you teach the course.

As you approach the end of the term, make sure your Canvas Gradebook accurately reflects students’ work and that all assignment grades are posted for student review.

If you’re using the Canvas gradebook

- Confirm that the grading information in your syllabus matches your Canvas gradebook. A helpful way to check is by entering the maximum point value for each column in the bottom gradebook row for your Test Student. (Note: If you intended to weight grades, but instead have a point-based total, you can still switch to weight grades by assignment group.)

- Enter all grades and post them for your students to review. By default, the Canvas gradebook totals only entered scores. Unsubmitted assignments show as dashes and are not factored into the final grade, which may inflate student totals. Enter zeros manually or apply a “missing submission policy” to assign zeros automatically

- Check your extra credit setup. You can add extra credit by creating an assignment worth zero points. This video shows how to set up an extra credit column for both a points-based and a weighted gradebook.

- Download a copy of your Canvas gradebook. It's good practice to keep a local copy for your records. However, be aware that you are removing FERPA-protected data from a secure site, so be mindful where you store this information.

Canvas users and non-Canvas users:

- Submit final grades. Grades entered in Canvas are not official. You must enter final grades through Banweb.

- Extend access for all students in your course. By default, students lose access to a Canvas course on the first day of the following term (i.e. Winter term courses will be available to students until the first day of Spring term). If you want all students to have access to your course for longer, you can change your Course End date.

- Extend access for a specific student. If you need to keep the course open for a specific student to complete the course, you’ll need to follow the instructions to grant an incomplete student access to a Canvas course.

Now that the term is over, take some time to relax and celebrate your course success!

In most cases, this won’t be the last time you teach this course. Take a moment to reflect on what worked—and what you might revise. OAI+ has many resources to support course improvement and experimentation. Here are some articles to explore:

Go a little further in your course development

The tasks listed in these checklists are just the basics, so don’t stop here! For more considered exploration, check out our many Teaching Guides for instructors at Portland State University.

You can also schedule a consultation with one of OAI’s instructional designers to help you enhance your course design. To schedule an appointment, submit a meeting request.

Frequently Asked Questions

This checklist seems very Canvas-heavy, but I'm not teaching online. Is this still useful to me?

Canvas isn’t just for online courses! Using Canvas for in-person or hybrid courses provides students with a consistent place to access materials, submit assignments, and track their progress in a course. For instructors, Canvas streamlines communication and simplifies the management of a course, making it easier to support students both inside and outside the classroom.

I'd like to start working through this checklist, but I don't see my Canvas course yet. When can I expect to have access to it?

Canvas course shells are typically created the week students begin registering for the upcoming term. Visit the PSU Academic Calendar, select the appropriate term, and look for the Priority Registration – Group A date. This is when you can expect to see courses begin to appear. Due to the number of classes created, Canvas course shell creation may take a few days. You may see courses show up on your Dashboard slowly throughout the week, instead of all at once. If you need a place to work on your course sooner or just want a sandbox where you can test new ideas, create a new Canvas course shell from your Canvas Dashboard.

How to support students with DRC accommodations

Contributors:Megan McFarland, Kari Goin Kono, Gracie Sheets, Disability Resource Center

Supporting students with disabilities through academic accommodations ensures equity, inclusion, and access at PSU. These accommodations remove barriers and support student belonging and success. This guide, developed with Disability Resource Center (DRC) staff, offers clear, actionable strategies for implementing common accommodations across teaching formats.

Faculty can expect to receive a Faculty Notification Letter when a student activates their accommodations each term. This letter outlines the specific accommodations the student is approved for (e.g., “Extended time (1.5x) on timed exams and quizzes”). It does not include the student’s diagnosis or medical information.

Faculty and students are both responsible for discussing how accommodations will be implemented. However, under federal law faculty may not ask students to disclose their disability or provide medical documentation to verify an accommodation. Conversations about accommodations should be handled discreetly and respectfully—for example, in a private meeting or via email rather than in front of the class.

How to communicate about accommodations

Do:

- Review the Faculty Notification Letter promptly when you receive it.

- Discuss how accommodations will be implemented—privately and respectfully.

- Contact the DRC with any questions or concerns about logistics or implementation.

- Treat accommodation conversations as a normal part of supporting student learning.

Don't:

- Don’t ask the student for their diagnosis or medical documentation.

- Don’t share a student’s disability status with others (including TAs or classmates).

- Don’t delay implementing an accommodation while waiting for a conversation.

- Don’t assume students will remind you about their accommodations each time—plan ahead.

If you have questions about how to implement an accommodation in your course, you can contact the DRC or the Office of Academic Innovaiton directly for support. While the DRC focuses on student support, OAI offers faculty consultations and usability reviews, as well as resources on accessibility. OAI can help troubleshoot, clarify course design ideas, and collaborate on solutions that uphold both student access and course integrity. Submit a request here.

What accommodations might students need?

In the sections below, you’ll find an overview of common DRC accommodations organized into five key categories:

Alternative formats

Assignments

Communication

Classroom

Testing

Each section highlights what the accommodation does, why it matters, and how to implement it.

Alternative formats

Some students access information in ways that don’t rely on vision or traditional print. This section offers guidance on how to design your materials for alternative formats so every student can meaningfully engage with course content.

Screen reader–accessible materials are structured so that all content (i.e., text, images, charts, and tables) can be read aloud and navigated by screen reading software. This requires proper formatting, such as heading styles, alt text, and readable document structures.

Accommodation purpose: This accommodation removes access barriers for students who are blind, have low vision, or experience print-related disabilities. It allows students to independently access and navigate course content using screen readers.

Tips for implementation:

- Use built-in heading styles to organize content clearly and consistently, just like chapters or headings in a book.

- Provide concise alternative text (alt text) for all images, charts, and meaningful visuals.

- Structure tables simply, with clear headers and no merged cells. Use only one row at the top that explains what each column means.

- Use true formatting tools (e.g., bullet list and column functions) rather than manual spacing or styling.

Tactile materials (e.g. Braille, textured diagrams, or haptic feedback) use the sense of touch to provide access for students who cannot access visual information.

Accommodation purpose: These accommodations use raised surfaces, textures, or other tactile cues to convey meaning. This ensures that students who are blind or have significant visual impairments can receive and interpret content in a non-visual way, preserving the meaning and structure of the original material.

Tips for implementation:

- Use heading styles and structural formatting to support accurate conversion.

- Provide detailed alt text for images and diagrams so that tactile versions convey essential information.

- Avoid inserting critical content into untagged images or visual-only formats that can’t be translated into tactile media.

Text-to-speech software converts written text into spoken words, allowing students to listen to digital content instead of reading it visually.

Accommodation purpose: Text-to-speech supports students with reading disabilities, attention-related challenges, or vision impairments by providing an alternative, auditory means of accessing course materials.

Tips for implementation:

- Follow the same formatting practices used for screen reader accessibility (e.g., heading styles, alt text, and list formatting).

- Only upload scanned PDFs or image-based documents that can be read by text-to-speech software.

- Provide digital versions of materials in editable formats (e.g., Word or tagged PDFs) when possible.

A note on roles: What do I do, and what does the DRC do?

The DRC is responsible for providing accessible versions of textbooks and ensuring students can access course materials in their preferred format. However, faculty play a key role in making supplemental materials—like journal articles, handouts, slides, and Canvas content—accessible. Because faculty are the content experts, they are best suited to add meaningful alt text or clarify complex visuals. If you’re unable to make a supplemental resource accessible and need DRC support, please provide the materials at least five days in advance to allow time for conversion. While OAI doesn’t provide direct remediation services, we’re happy to support you through the process.

Assignments

Assignment accommodations help students manage executive functioning, communication, and processing needs. This section shares strategies for offering clarity, flexibility, and alternative options that maintain academic integrity while removing unnecessary barriers to learning.

Provide assignment details, requirements, and deadlines earlier than usual to support planning and time management.

Accommodation purpose: This practice minimizes barriers for students who experience difficulties with executive functioning, memory, or health fluctuations that impact their ability to manage timelines.

Tips for implementation:

- Post assignment descriptions and deadlines as early as possible.

- Ensure updates or changes to assignments are communicated promptly and in multiple formats.

- Provide written assignment timelines and expectations to prevent misunderstandings.

When disability-related barriers make group participation difficult, students may complete an alternative individual assignment designed to meet the same learning objectives.

Accommodation purpose: Providing alternative options ensures students are not excluded from meeting course expectations due to challenges with communication, coordination, or sensory environments.

Tips for implementation:

- When possible, design alternative individual assignments in advance to prevent delays.

- If collaboration is a core learning objective, discuss possible adjustments with the student and the DRC.

- Be clear about expectations for the individual assignment and ensure it aligns with the learning outcomes of the original group work.

- Maintain confidentiality; do not disclose to peers why a student is completing individual work.

All assignment expectations and instructions must be provided in writing, even if they are discussed verbally during class or meetings.

Accommodation purpose: Providing key information in writing supports students who experience challenges with auditory processing, memory, or attention, and ensures equitable access to assignment information.

Tips for implementation:

- Provide assignment details and instructions consistently through written formats (such as a Canvas announcement, email, or printed handout).

- Avoid relying solely on verbal announcements to communicate expectations.

- Use clear, consistent templates or formats to present assignment information to reduce confusion.

Include detailed instructions, deadlines, grading criteria, and any submission expectations.

Students are allowed reasonable extensions (often 2–3 days) on assignments when disability-related impacts interfere with their ability to meet standard deadlines.

Accommodation purpose: Additional time allows students to demonstrate mastery of content while accounting for disability-related barriers that may temporarily affect their work pace.

Tips for implementation:

- Clearly communicate the process for requesting an extension, including how far in advance to notify you if possible.

- Acknowledge that students may not always be able to provide advance notice due to the nature of their disability.

- Be flexible with automated due dates in Canvas and be prepared to adjust them manually as needed.

Communication

For some students, access to course content depends on communication supports like captions, interpreters, or amplification. This section outlines ways to ensure your spoken and visual materials are accessible to students who are Deaf, hard of hearing, or have other information processing-related access needs.

Accessible media includes videos or audio content with accurate captions or transcripts to ensure that spoken language is available in a visual format.

Accommodation purpose: Captions and transcripts are essential for students who are Deaf or hard of hearing, as well as for students with auditory processing challenges or language-related learning disabilities. They support equitable access to audio content.

Tips for implementation:

- Use a hosting platform that offers captioning (e.g., MediaSpace or Zoom).

- Review and edit auto-generated captions for accuracy and completeness.

- Provide transcripts for audio-only content like podcasts or recorded lectures.

- Request accessible media through the DRC

An amplification device increases the volume and clarity of sound for students with hearing impairments.

Accommodation purpose: These devices reduce background noise and enhance speech comprehension by delivering optimized audio directly to the listener, often through a hearing aid or a personal sound amplification device.

Tips for implementation:

- Speak clearly and at a moderate pace during lectures or recordings.

- Test audio equipment and microphone placement to reduce background noise.

- When possible, ensure captions are available to supplement audio amplification.

ASL interpreting provides a real-time translation of spoken English into American Sign Language, a fully distinct visual-spatial language used by many in the Deaf community and others who have difficulty accessing spoken language.

Accommodation purpose: Interpreting ensures that students who are Deaf, hard of hearing, or who experience other disabilities that impact a person’s access to spoken language can fully access spoken content and engage in classroom discussion.

Tips for implementation:

- Work with the DRC to coordinate interpreter logistics in advance.

- Speak at a natural pace and avoid covering your face so interpreters can follow clearly.

- Address the student directly, not the interpreter, when communicating.

Communication Access Realtime Translation (CART) provides live, synchronous captions of spoken content during classes, meetings, or events.

Accommodation purpose: CART provides synchronized text from spoken words during a live event. This allows people to read text of any spoken words used.

Tips for implementation:

- Turn on captioning features in Zoom , Google Slides , or select the “always use subtitles” option in PowerPoint to ensure participants can follow along with your presentation during a live event.

- Ensure microphones are working properly and limit overlapping speakers.

- Pause briefly when switching topics to allow the captions to stay caught up.

Audio descriptions are spoken narrations of important visual information in video content (e.g., on-screen text, actions, or scene changes) that are not conveyed through dialogue.

Accommodation purpose: Audio descriptions provide blind or low-vision students with access to visual elements that are essential to understanding the content of the video.

Tips for implementation:

- Verbally describe key visuals (e.g., graphs, on-screen text, images) during your recordings.

- Use clear, concise language that fits naturally within pauses in speech.

Classroom

Whether you teach in-person, online, or hybrid, classroom accommodations help ensure students can physically and cognitively access the learning environment. In this section, you’ll find guidance on how to implement supports like flexible attendance, accessible seating, and note-taking assistance with confidence and care.

The classroom must have seating or workstations that meet a student’s disability-related needs (e.g., adjustable-height tables, ergonomic chairs).

Accommodation purpose: Accessible furniture provides physical access and comfort, reducing barriers to participation caused by standard classroom furnishings.

Tips for implementation:

- Leave accessible furniture in place once assigned.

- Avoid using accessible furniture for general seating or storage.

- Contact the DRC immediately if the furniture is moved or missing.

Students are provided an alternative assignment to replace an oral presentation if disability-related barriers prevent participation.

Accommodation purpose: Alternative options for presentations ensure students can meet course objectives in ways that are accessible to their abilities, particularly where speech, anxiety, or sensory disabilities are factors.

Tips for implementation:

- Design alternatives that align with the learning objectives of the presentation. For example, if the original goal is to assess how well students can explain a concept and engage an audience, you might offer a recorded video, a detailed slide deck with speaker notes, or a one-on-one presentation in a lower-stress environment.

- Use the same grading criteria or rubric for both the original and alternative assignments to ensure consistency and fairness.

- Clearly communicate expectations for the alternative assignment, including due dates, format, and how it will be evaluated.

An assistant may accompany a student to provide physical or communication support in classroom or lab settings.

Accommodation purpose: Having another person to assist facilitates full participation in environments where manual tasks, mobility, or communication may otherwise be a barrier.

Tips for implementation:

- Avoid calling attention to the assistant’s presence in front of the class. Treat them as a natural part of the learning environment, rather than someone who needs explanation or justification.

- Speak to the student, not the assistant, during instruction, group work, or check-ins. The assistant is there to support access, not to serve as a stand-in.

- Avoid asking the assistant to perform tasks unrelated to the student’s access needs.

- Keep any planning or questions about the assistant private (e.g., in email or one-on-one meetings) instead of bringing it up during class time.

Students are permitted to take breaks during class or lab activities without penalty.

Accommodation purpose: The ability to take breaks supports students whose disabilities require intermittent rest, movement, or symptom management.

Tips for implementation:

- Position the student near the door when possible so they can exit and re-enter with minimal disruption.

- Avoid drawing attention to the student when they leave or return. Continue teaching as normal rather than pausing or commenting on the break.

- If the student will miss important material during breaks, offer to share notes or allow them to audio-record that portion of class so they can review it later. You can also point them to Canvas resources or slides.

Instructors should not call on the student unless the student has indicated readiness by raising their hand.

Accommodation purpose: Being able to decide when they can be called on prevents stress, anxiety, or access issues for students who experience communication-related disabilities.

Tips for implementation:

- Include this expectation in your teaching notes or attendance roster so you remember not to call on the student spontaneously, even during group discussions or cold-call activities.

- Adjust any teaching strategies that involve randomly selecting students to speak. For example, use volunteer-based discussions, polling tools, or small-group activities instead.

- Brief any guest speakers, co-instructors, or teaching assistants on the accommodation to ensure the student’s accommodation is respected consistently.

Provide printed materials or classroom documents in a larger font size as specified by the student’s accommodation plan.

Accommodation purpose: Enlarging the print on written materials supports students with low vision or other visual impairments.

Tips for implementation:

- Coordinate with the DRC to determine the preferred font size and format.

- Provide accessible copies of any printed handouts or exams.

- Allow digital copies whenever possible

Students may receive extended time to complete in-class assignments due to disability-related impacts on processing speed, stamina, or mobility.

Accommodation purpose: Extending the allotted time for in-class activities provides equal opportunity to demonstrate knowledge without time-based barriers.

Tips for implementation:

- Clarify expectations and deadlines for in-class assignments early.

- Arrange alternate submission options if class time constraints are inflexible.

- Work with the student to identify a plan in advance whenever possible.

Students may occasionally miss class due to disability-related reasons without penalty, as approved through the DRC process.

Accommodation purpose: Flexible attendance expectations allow students to manage dynamic, unpredictable symptoms or medical treatments without losing academic standing.

Tips for implementation:

- Clarify your communication expectations early. Let students know how you prefer to be notified of absences (e.g., via email, Canvas message), keeping in mind that flexibility is also important.

- Collaborate with the student on how they can stay engaged if they miss a class. This might include accessing lecture slides, recorded sessions, discussion boards, alternative readings, or a brief written reflection on missed content.

- Be transparent about essential course components. If certain class sessions, activities, or participation elements are considered essential to meeting learning outcomes, make that clear in the syllabus and offer options for how students can meet those requirements if they miss a session.

Students must be given access to presentation slides or lecture materials prior to the start of class.

Accommodation purpose: Having access to class materials in advance supports students with disabilities that impact note-taking, processing speed, or attention.

Tips for implementation:

- If your slides aren’t finalized until just before class, consider sharing a rough draft a few days in advance with key terms, frameworks, or visuals that are unlikely to change.

- Use recurring templates or slide structures to make it easier to reuse and share consistent materials in advance, even if the specific examples or data change each week.

- Upload materials to Canvas or email them in advance when feasible, and communicate clearly with the student about when they can expect access. Let them know if content will be updated and when the final version will be available.

- Consider offering an outline or lecture guide that previews the topics or learning objectives for the day in place of full slides if needed.

A peer note taker may be recruited to share their class notes with the student.

Accommodation purpose: Having another person take and share class session notes provides equitable access to lecture content for students who cannot take their own notes effectively due to disability.

Tips for implementation:

- Facilitate recruitment by making a general class announcement (without naming the student).

- Coordinate with the DRC to manage note distribution securely.

- Use teaching strategies that support note-taking for all students. These practices also improve the quality of peer-provided notes:

- Clearly signal transitions and major points by saying them aloud and/or writing them down.

- Use headings, bullet points, or outlines on slides or whiteboards to visually structure the lecture.

- Repeat or rephrase key ideas to give students time to catch up or clarify their notes.

- Avoid moving too quickly through dense information without breaks or summaries.

Students may attend a class remotely in real time when disability-related impacts prevent in-person participation.

Accommodation purpose: When students can access your class remotely, it allows them to fully participate when physical attendance is difficult or unsafe. This accommodation can support students with a wide range of access needs, such as chronic illness, mobility limitations, severe fatigue, post-surgical recovery, or heightened sensitivity to environmental stimuli (e.g., light, noise, or scent). It removes barriers related to commuting, navigating physical campus spaces, or managing flare-ups of unpredictable symptoms that could otherwise force students to miss class entirely.

Tips for implementation:

- Avoid assumptions. If a student uses this accommodation regularly, remember that it is based on documented disability-related need, not convenience. Treat remote participation as a legitimate form of engagement.

- Coordinate logistics early. Work with the student and the DRC to determine the best way to access class remotely.

- Make sure the Zoom link is easy to access and consistently available.

- Ensure audio and visuals are accessible. Speak clearly and repeat in-person comments or questions so remote students can follow the conversation. If you’re writing on the board or using physical demonstrations, consider offering a verbal description or sharing a digital version of the material.

- Create opportunities for remote participation. Invite remote students to participate in discussions via chat or voice.

- Consider assigning an in-person classmate to monitor the chat and help flag questions or comments.

- Set expectations clearly. Let students know how they should participate remotely: whether cameras are expected to be on, how they should signal they want to speak, and how to notify you if technical difficulties arise.

- Be flexible with interactive activities. If you’re planning group work or hands-on activities, think in advance about how remote students can join (e.g., breakout rooms, Google Docs collaboration, alternate formats).

Testing

Traditional exams can pose a range of barriers, from time pressure to sensory overload to inaccessible formats. This section outlines accommodations that help students demonstrate what they’ve learned in ways that reflect their knowledge, not their disability-related limitations, and offers tips to simplify implementation.

Extended time provides students with additional time to complete exams or assignments. It may also allow for breaks during testing to support stamina and focus.

Accommodation purpose: This accommodation supports students who process information more slowly, require more time for reading, writing, or typing, or who need breaks due to physical, cognitive, or sensory disabilities. It allows students to demonstrate their knowledge without the barrier of artificial time constraints.

Tips for implementation:

- Plan ahead for extended time needs. If you’re using Canvas quizzes, use the “Moderate Quiz” function to adjust the time for individual students. If your assessments are in-person, coordinate with the DRC and Academic Testing Services early to arrange proctoring support.

- Clarify expectations in advance and avoid placing unnecessary administrative burdens on the student.

This accommodation allows students to complete exams in an environment with minimal sensory or cognitive distractions.

Accommodation purpose: A quieter, more controlled setting can help students with attention-related disabilities or sensory processing challenges better focus, manage anxiety, and complete work without unnecessary interference.

Tips for implementation:

- Coordinate with the DRC and Academic Testing Services for alternate testing locations.

- Offer remote or take-home assessments when appropriate, with flexible access windows.

- Ensure your Canvas course materials are clearly organized to minimize cognitive load.

This accommodation allows students to use a reference sheet, class materials, or a dictionary during exams.

Accommodation purpose: This supports students with disabilities that affect memory retrieval, vocabulary recall, or spelling (e.g. dyslexia or dysgraphia) by reducing barriers and instead focusing on the individual’s understanding of the core concepts.

Tips for implementation:

- Communicate discreetly and collaboratively with the student about what materials are permitted. Clarify expectations with the student privately and adjust their exam conditions accordingly.

- Ensure access to necessary materials. If the student is allowed course notes, make sure your lectures or slide decks are accessible and available in advance. If you’re permitting a dictionary, ensure students know which one(s) are acceptable (e.g., online vs. physical, English only vs. bilingual).

Students may need to take exams at a different time than the rest of the class, either through PSU’s testing center or within an extended availability window in Canvas.

Accommodation purpose: This allows for flexible scheduling to meet medical, sensory, or processing needs while ensuring a quieter or more supported testing experience.

Tips for implementation:

- Use Canvas to offer extended testing windows or flexible start times.

- Connect with Academic Testing Services for proctoring accommodations, as well as a guide to enhancing exam accessibility and inclusivity through Canvas.

- Submit testing requests promptly, as the DRC and testing center require advance notice and scheduling coordination.

This accommodation allows a student to complete an exam in multiple sittings or sections, with breaks in between.

Accommodation purpose: It supports students who experience fatigue, cognitive overload, or medical issues that make it difficult to complete an entire exam in one sitting. It ensures they can demonstrate their knowledge over time and are not limited by stamina.

Tips for implementation:

- Break the exam into clearly defined sections in Canvas and allow students to complete them with pauses between.

- Coordinate timing with the student and/or DRC to ensure breaks don’t impact content exposure or exam security.

- Be flexible with grading timelines if students require extra time to complete all sections.

Students may eat or drink during testing as a necessary part of their disability management plan.

Accommodation purpose: Eating or drinking during assessments helps students maintain blood sugar, energy, or hydration levels. This can prevent health complications and support cognitive performance during long or stressful testing periods.

Tips for implementation:

- Remind students to choose quiet, non-disruptive options to minimize distraction.

- If other students are impacted, consider alternative seating arrangements.

Permits the use of a basic calculator with addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division functions.

Accommodation purpose: This removes or minimizes barriers related to basic arithmetic computation (addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division) so that an individual’s understanding of deeper mathematical concepts and problem-solving skills can be more accurately assessed. Specifically, it allows instructors to assess whether a student understands the underlying concepts and can apply them to solve problems, rather than just their ability to perform basic calculations accurately and quickly without tools.

Tips for implementation:

- If the exam is online, allow the use of a virtual four-function calculator or embed one in the test instructions.

- If other students are not allowed to use a calculator, ensure that the accommodation is implemented discreetly (e.g., providing a paper test version or calculator only to the eligible student without announcing it to the class).

Supporting students with disabilities isn’t about perfection. It starts with awareness, flexibility, and a collaborative mindset. By understanding the purpose behind DRC accommodations and implementing them with care, you help remove barriers that might otherwise limit student success. Your efforts not only uphold students’ rights but also strengthen your teaching, build trust, and create a more inclusive academic community where all students can thrive.

Learn more

Portland State University resources

Guidance on implementing accommodations and working with the DRC.

General information about working with the DRC when you have a student with accommodations

Information on how to support students using Academic Testing Services for accommodations.

University-wide accessibility resources, policies, and contact information.

National and External Resources

Resources for postsecondary faculty to better support students with disabilities.

A detailed framework for applying Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles in higher education.

National organization offering professional development, guidance, and resources on disability in higher education.

Overview of foundational accessibility standards for digital content.

Tools and Tutorials

Comprehensive explanations and tutorials for creating accessible digital materials.

Comprehensive explanations and tutorials for creating accessible digital materials.

Guidance on accessibility in Google Docs, Slides, Forms, and more.

Supporting students through trauma in the classroom

Contributors:Megan McFarland, Student Health And Counseling, Trauma Informed Oregon, and Members of the Suicide Prevention Collaborative at Portland State University

Traumatic events—whether campus-wide incidents, local tragedies, or community disruptions—can impact students in profound and varied ways. We may find ourselves navigating students’ emotional responses, misinformation, shifting academic needs, and our own reactions, all while continuing to lead a classroom. This resource provides guidance on how to acknowledge trauma, foster safety and support, and offer structure and care within an instructional setting.

Common emotional and behavioral responses to trauma

Everyone responds to trauma differently; there is no single “right” way to process distress. Trauma may appear in various ways:

- Emotional: Irritability, anger, anxiety, sadness, guilt, emotional numbness

- Cognitive: Difficulty concentrating, trouble making decisions, memory lapses

- Behavioral: Increased restlessness, withdrawal, avoidance, hyper-productivity

- Physical: Fatigue, headaches, muscle tension, sleep disturbances

- Social: Increased need for connection or, conversely, isolation from peers

Avoid making assumptions about how students—or colleagues—are processing trauma.

How to support students

You don’t need to have all the answers to support students. It begins with presence, flexibility, and care. The strategies below offer tangible ways to foster emotional safety, support autonomy, and guide students toward healing while respecting the varied ways trauma can manifest.

Acknowledge the event in class

Create space for optional discussion or reflection. Ensure students do not feel pressured to engage.

Example response: “I want to acknowledge the recent events in our community. This may be affecting each of you differently, and it’s okay to take time to process. If you’d like to talk or reflect, I’ll make space for that today.”

Consider a brief mindfulness practice or a written reflection prompt to support private engagement.

Extend grace and normalize emotional responses

Promote self-compassion by reassuring students that different reactions are normal.

Example response: “Trauma affects everyone differently, and there is no ‘right’ way to feel. If you’re struggling, please know that I am here to support you, and we have campus resources available if you need them.”

Encourage a similar approach among colleagues, teaching assistants, and peer leaders.

Offer brief mindfulness exercises

Even a few minutes of grounding or quiet reflection can help students self-regulate and re-engage. These short mindfulness exercises can be easily led at the beginning or end of class to support emotional balance and create space for care. They are optional, adaptable, and inclusive. You may adapt the language to suit your teaching context.

Instructions: “Let’s take a moment to ground ourselves by focusing on our five senses. You don’t have to close your eyes, but if you’d like to, you can. Take a deep breath in and out. Now, silently name:

- Five things you can see around you

- Four things you can feel (your chair, clothing, temperature, etc.)

- Three things you can hear

- Two things you can smell (or recall a comforting scent)

- One thing you can taste (or remember a favorite flavor)

Take one more deep breath in and out. Thank you for taking that moment for yourself.”

Instructions: “If you’d like to, take a moment to focus on your breathing. We’ll use a simple technique called box breathing. Imagine drawing a square in your mind as we breathe:

- Inhale for a count of four.

- Hold the breath for a count of four.

- Exhale for a count of four.

- Hold for a count of four again.

Let’s repeat that two more times. If you prefer, you can simply sit in silence and breathe at your own pace.”

Instructions: “Take a moment to send kindness to yourself and to others. If it helps, place a hand over your heart or take a deep breath. Silently repeat these words to yourself:

- May I be kind to myself in this moment.

- May I allow myself to feel whatever I need to feel.

- May I offer the same kindness to others.

If you know someone who’s struggling, you can imagine sending them kindness as well. Let’s take one more deep breath together before we move forward.”

Use reflection prompts to support private processing

Not all students will want to share their experiences out loud, but many may benefit from quiet, private opportunities to reflect. Writing exercises can offer a low-pressure way to process emotions, build self-awareness, and tap into inner strengths. The following prompts are adaptable and can be used at the start of class, during a pause, or as part of an asynchronous activity. Emphasize that sharing is optional and that these are for personal reflection, not evaluation.

“Take a few minutes to write a letter to yourself as if you were comforting a close friend. What words of encouragement or support would you offer? If this moment is difficult, what gentle reminder might you give yourself?”

“On a piece of paper, draw a simple outline of a person (or write words across the page). Without judgment, notice where emotions show up in your body. If you’re feeling anxious, where do you feel it? If you’re feeling sadness, does it have a place? You don’t have to share this with anyone, but noticing where emotions sit in our bodies can help us process them.”

“Even in difficult times, we carry strengths and support systems with us. Take a moment to write about one or two things that bring you comfort or resilience. This could be a person, a place, a memory, or a personal strength you’ve relied on in the past.”

Balance flexibility and structure

Trauma can create a sense of helplessness.Some students may struggle with focus, attendance, or deadlines, while others may find normal routines grounding. Offering choices can help students regain a sense of control. We can and should provide reasonable flexibility while maintaining structure. Support can look like:

- Adjusting workload (e.g., asynchronous options)

- Providing structured work time or small executive functioning supports

- Offering sensory supports (e.g., fidgets, lighting, calming music)

- Connecting students with support services

- Sharing meals or mutual aid boards

Facilitate social processing and release

We can offer—but not require—opportunities for students to process emotions in different ways:

Social processing options

- Group discussions about the impact of the event or personal experiences

- Collaborative art using prompts related to trauma, healing, or community

- Check-ins using emotion wheels, scales or symbols

Social release options

- Games that evoke laughter and play

- Group physical activity (e.g., dance, yoga)

- Shared meals or time with animals

- Lighthearted videos or communal creative expression

Support individual students one-on-one

Some students may want one-on-one conversations, especially if they’re more directly affected. In these moments, it’s helpful to offer calm, compassionate presence without trying to “fix” anything. The following scripts can guide supportive check-ins, helping you respond with empathy while staying within your role as an instructor. Adjust the wording to fit your voice and the student’s needs.

Example response: “That’s completely understandable. Trauma can make it hard to concentrate. Let’s talk about some adjustments that might help—like breaking tasks down or shifting deadlines.”

Example response: “It’s normal to feel overwhelmed, but please be gentle with yourself. You couldn’t have predicted this. If you’re open to it, I can help you find someone to talk to.”

Example response: “I am sorry this has been so difficult. If you need to talk or take time for yourself, please let me know how I can support you. Have you had a chance to connect with a counselor or someone you trust?”

Refer students to support services

We don’t have to be counselors to help students access meaningful support. One of the most impactful things we can do is normalize help-seeking and offer to connect students with resources. The following strategies and sample language can help you encourage students to explore counseling, peer support, or identity-based services, especially if they seem unsure about reaching out on their own.

- Encourage students to use peer support programs or identity-based support spaces.

- Emphasize that using mental health resources is a sign of strength, not weakness.

Example Response: “I know this is a really difficult time, and it’s completely okay to seek support. SHAC offers free counseling, and I’d be happy to help you connect with someone who can assist.”

Portland State University resources

Confidential mental health support for faculty and staff.

Available for student referrals, but can also provide faculty guidance on supporting grieving students.

Trauma-Informed Oregon collaborates with providers, individuals with lived experience, and families to advance trauma-informed policies and practices in health systems while promoting strategies for wellness and resilience

Confidential mental health support for faculty and staff.

Office of the Dean of Student Life

Guidelines for faculty when responding to a student death or tragedy

External mental health and crisis resources

Crisis lines

- Lines for Life (Oregon-based crisis line): Call 1-800-273-8255

- Multnomah County Mental Health Crisis Line: 24/7 support at (503) 988-4888. Crisis Text Line: Text HOME to 741741

Clinics & Centers

- Cascadia Urgent Walk-in Clinic: Check website for current hours and contact information. Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (Call, text or chat): Dial 988

- Portland Mutual Aid Network – A volunteer-led group that distributes food, personal care items, and survival supplies to unhoused individuals, prioritizing direct engagement and community-driven support.

- Mutual Aid PDX – A network compiling mutual aid resources across Portland, including food distribution, tenant support, and direct financial assistance initiatives.

- The Dougy Center – Provides support groups and resources for children, teens, young adults, and families grieving a death. Services are designed to offer a safe space for sharing experiences and finding support.

Culturally-specific crisis resources

- People of Color Crisis Text Line (The Steve Fund): Text STEVE to 741741

- Amala Muslim Youth Hopeline: 1 (855) 952-6252 (1-855-95-AMALA)

- Ayuda en Espanol: 24/7 support at (888) 628-9454

- Thrive Text Line (support for people with experiences of oppression): Text THRIVE to 1 (313) 662-8209

- Amala Muslim Crisis Text Line: Text SALAM to 741741

- The Trevor Project Crisis Line (Mental health support for LGBTQ young people): Call (866) 488-7386 or text "START" to 678-678

- Warm lines that don't use police

Supporting ourselves after trauma: A guide for faculty

Supporting ourselves after trauma

A guide for faculty

Contributors:Megan McFarland, PSU Student Health And Counseling, Trauma Informed Oregon, and Members of the Suicide Prevention Collaborative at Portland State University

Faculty and staff often play a key role in supporting students during times of trauma or crisis. In the process, we may overlook our own emotional needs. This guide offers tools to help faculty recognize, respond to, and recover from the personal impact of trauma in the community.

Faculty experience trauma too

Faculty and staff may experience personal grief or secondary trauma while managing academic responsibilities and supporting students. It’s important to seek support, model healthy coping strategies, and remember that our role is to provide structure and connection—not to serve as a counselor.

Common trauma responses

Everyone processes trauma differently. Common responses may include:

- Irritability or quick anger

- Numbness or disconnection

- Anxiety or increased urgency

- Sadness or tearfulness

- Fatigue or low energy

- Restlessness or hyperactivity

- Physical aches and pains

You might feel fine at first, then overwhelmed days later. There’s no correct timeline.

Trauma processing strategies for faculty

Supporting students through trauma while managing our own well-being can be deeply taxing. Prioritize your needs by practicing self-compassion, setting clear boundaries, and seeking support. The strategies below offer both immediate tools and long-term approaches. Try different techniques and pay attention to what brings relief, connection, or clarity—your needs may shift over time.

1. Prioritize self-compassion and boundaries

- Extend yourself grace and non-judgment—your emotions and behaviors may look different than expected.

- Set emotional and professional boundaries while supporting students. Example scripts:

“I care about what you’re going through, and I want to support you. I also want to connect you with the best resources. Would you be open to meeting with a counselor?”

“I want to be here for you, but I also need to take care of myself. Can I check in with you later?”

Allow yourself to ask for support from colleagues when needed.

2. Try processing and releasing strategies

Everyone processes trauma differently. Consider combining language-based (linguistic) and body-based (somatic) techniques. Reflect on how each affects your well-being.

Language-based strategies

For processing:

- Freewrite by setting a timer for 5-15 minutes, and writing without editing.

- Journal with prompts related to grief, loss, and community.

- Talk aloud while alone or in a trusted space.

- Cry, yell, or express strong emotions verbally.

- Watch emotional media (e.g., sad movies) to facilitate release. If you feel “stuck” in sadness, set a limit (e.g., one episode, one movie), and follow it with a “releasing” activity.

Releasing and shifting:

- Journal about joy, connection, and safety.

- Sing or listen to uplifting music.

- Say affirmations aloud (e.g., “I am safe, I am cared for”).

- Watch light or humorous media.

- Engage in simple mental tasks (e.g., crossword puzzles, data entry).

Body-based strategies

For processing:

- Release stored tension — punch a pillow, throw ice into a bathtub.

- Take warm baths or showers to soothe your nervous system.

- Engage in self-massage, yoga, or stretching.

- Listen to emotionally intense music (e.g., sad, angry, or cathartic music). If you feel “stuck” in these emotions, set a time limit (e.g., three songs) and transition to a releasing activity.

- Create art about grief, loss, or connection.

Releasing and shifting:

- Exercise (e.g., running, weightlifting, cardio workouts).

- Take cold showers or plunges for nervous system reset.

- Complete grounding exercises (e.g., breathing techniques, mindful movement) such as ventral vagal techniques, mental grounding exercises, or physical grounding exercises.

- Dance or listen to joyful music.

- Create art that reflects joy, love, or safety.

- Complete simple motor-based tasks (e.g., cleaning, organizing, puzzles).

- Spend time in nature to regulate emotions.

- Wear clothing that feels comfortable and grounding.

Reflect on your grief and resilience

“After several traumatic events in my life and career, I’ve noticed I become calm and focused in a crisis. That helps me support others and make quick decisions. But I also know the emotional toll hits 1–3 days later, leaving me low-energy and anxious.

Now I try to complete cognitively demanding tasks the day after a crisis so I can rest and process later. When emotions surface, I journal, exercise, maintain routines, eat protein-rich foods, ask colleagues for executive function support, and attend therapy.”

– Anonymous, Adjunct Faculty, College of Education

The hard truth is that traumatic events will happen again over the course of a career in education. Reflecting on past experiences can help build resilience for future events.

Guiding questions:

- What impact did the loss have on my brain and body?

- Did I feel tired, numb, foggy, anxious, dissociated, or hyper-focused?

- What coping strategies helped?

- Did linguistic or body-based techniques feel more effective?

- Did I need more solo or social processing?

- What activities provided relief? What activities made me feel worse?

When to seek additional support

If distress significantly impacts daily functioning for more than two weeks, please consider accessing formal support like counseling, group therapy, or a consultation with your primary care provider.

Signs that additional support may be needed:

- Ongoing disruptions to sleep, appetite, or focus

- Persistent irritability or emotional numbness

- Feeling stuck in a loop of distressing thoughts

- Increased isolation or avoidance of usual responsibilities

- Difficulty regulating emotions in class or professional settings

Portland State University resources

Confidential mental health support for faculty and staff.

Confidential mental health support for faculty and staff.

Office of the Dean of Student Life

Available for student referrals, but can also provide faculty guidance on supporting grieving students.

Trauma-Informed Oregon collaborates with providers, individuals with lived experience, and families to advance trauma-informed policies and practices in health systems while promoting strategies for wellness and resilience

External mental health and crisis resources

Crisis lines

- Lines for Life (Oregon-based crisis line): Call 1-800-273-8255

- Multnomah County Mental Health Crisis Line: 24/7 support at (503) 988-4888. Crisis Text Line: Text HOME to 741741

Clinics & Centers

- Cascadia Urgent Walk-in Clinic: Check website for current hours and contact information. Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (Call, text or chat): Dial 988

- Portland Mutual Aid Network – A volunteer-led group that distributes food, personal care items, and survival supplies to unhoused individuals, prioritizing direct engagement and community-driven support.

- Mutual Aid PDX – A network compiling mutual aid resources across Portland, including food distribution, tenant support, and direct financial assistance initiatives.

- The Dougy Center – Provides support groups and resources for children, teens, young adults, and families grieving a death. Services are designed to offer a safe space for sharing experiences and finding support.

Culturally-specific crisis resources

- People of Color Crisis Text Line (The Steve Fund): Text STEVE to 741741

- Amala Muslim Youth Hopeline: 1 (855) 952-6252 (1-855-95-AMALA)

- Ayuda en Espanol: 24/7 support at (888) 628-9454

- Thrive Text Line (support for people with experiences of oppression): Text THRIVE to 1 (313) 662-8209

- Amala Muslim Crisis Text Line: Text SALAM to 741741

- The Trevor Project Crisis Line (Mental health support for LGBTQ young people): Call (866) 488-7386 or text "START" to 678-678

- Warm lines that don't use police

More about managing trauma as educators

Designing effective assessments

Designing effective assessments

A foundations guide for Portland State faculty

Contributors:Raiza Dottin, Megan McFarland

Assessment plays a vital role in higher education, serving as a bridge between teaching practices and student learning outcomes. At its core, assessment refers to any activity, assignment, or tool that evaluates what students have learned and how they apply that knowledge. Assessments can take many forms—exams, projects, papers, reflections, and other course assignments. Effective assessment helps us identify where students are excelling, where they may need additional support, and how we can adapt our teaching practices to meet their needs. In this article, you will find concrete strategies and examples to refine your teaching approaches, improve course content, and promote student success through effective assessment.

What is assessment design?

Assessment design involves the intentional planning and structuring of activities, assignments, and tools that measure student learning and evaluate the effectiveness of educational programs. While assessment itself includes a range of practices—from direct evaluations of student work to indirect measures like surveys and reflections—assessment design focuses on aligning these assessments with your course learning objectives. Thoughtful assessment design ensures that the methods you choose provide meaningful insight into student progress and that your instructional strategies effectively support the outcomes you want for your students.

Assessment is the process of gathering and analyzing evidence to understand and improve student learning and academic programs.

Why is quality assessment design important?

Assessment is a cornerstone of quality education, providing critical insights into the efficacy of teaching methods and how well course objectives align with student needs. It helps identify learning gaps, refine instruction, and support continuous improvement. Notably, assessment promotes transparency and accountability—ensuring students, faculty, and institutions can work toward shared goals.

As told by an instructor:

“Incorporating ongoing feedback into my course design has been invaluable. I ask students to record reflections every two weeks responding to four prompts—commenting on content and giving feedback on what’s working or not. I also name my positionality and reassure students that I truly use their input to improve their experience. In ED 519: Inclusive Secondary Classrooms, their feedback helped me diversify readings and refine a cross-teaching assignment to encourage student agency and self-directed learning through authentic learning tasks. Afterward, I asked if they found it useful and whether they’d do it again. The overwhelming response was yes—which genuinely surprised me! I’ll definitely continue this practice.”

- Grant Scribner, Adjunct Faculty, PSU College of Education

As told by an instructor:

“Incorporating ongoing feedback into my course design has been invaluable. I ask students to record reflections every two weeks responding to four prompts—commenting on content and giving feedback on what’s working or not. I also name my positionality and reassure students that I truly use their input to improve their experience. In ED 519: Inclusive Secondary Classrooms, their feedback helped me diversify readings and refine a cross-teaching assignment to encourage student agency and self-directed learning through authentic learning tasks. Afterward, I asked if they found it useful and whether they’d do it again. The overwhelming response was yes—which genuinely surprised me! I’ll definitely continue this practice.”

- Grant Scribner, Adjunct Faculty, PSU College of Education

How to design quality assessments

In this section, we apply the principles of backward design, an approach that begins by identifying desired learning outcomes before developing assessments and instructional strategies to support those goals (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005).

1. Define clear learning objectives

Clear learning objectives, also sometimes referred to as “learning outcomes,” clarify what students should know or be able to do by the end of a lesson, module, or course. Well-crafted objectives use measurable verbs and focus on specific knowledge or skills.

Start with course goals: Identify the overarching goals of the course by asking yourself, “What should students know, do, or believe after completing this course?” In many cases, course-level learning objectives are set at the department or university level—such as through Faculty Senate-approved curriculum—and may not be easily changed. However, you can still design assessments and assignments that align with these goals while tailoring the day-to-day learning activities and module-level objectives to your course context. Focusing on what success looks like for students in your particular classroom can help make assessment design more actionable and relevant.

Break goals into specific outcomes: Use frameworks like Bloom’s Taxonomy or Fink’s Taxonomy to write specific, measurable, and student-focused learning outcomes (Fink 2013).

- Instead of: “Students will understand ecosystems”

- Use: “Students will analyze the interdependence of organisms in ecosystems using case studies.”

Use the ABCD Framework: Ensure each learning outcome specifies:

- Audience: Who is learning? (e.g., “students”)

- Behavior: What will they do? (e.g., “analyze ecosystem dynamics”)

- Condition: Under what context? (e.g., “using case studies”)

- Degree: How well must they perform? (e.g., “apply principles accurately in 3 out of 4 examples”).

Limit the number of objectives: Focus on 3-7 outcomes per course to keep assessment measurable

Example learning objectives

Students will…

- Identify and explain the key components of the U.S. Constitution.

- Analyze primary source documents to construct a historical argument.

- Evaluate the credibility of scientific research articles.

2. Align assessments with learning outcomes

In assessment, alignment means that the task students complete directly matches what the learning outcome says they should demonstrate.

Match each outcome with an assessment:

- Outcome: “Evaluate research methods” → Task: critique a research article

- Outcome: “Demonstrate effective oral communication” → Task: deliver a presentation

Use the right type of assessment:

- Direct assessments (e.g., papers, projects) measure observable skills.

- Indirect assessments (e.g., surveys, reflections) offer insight into student attitudes or perceptions.

Ensure appropriate scaffolding: Lectures, activities, and readings should prepare students for assessments. For example, if students must write a research paper, include instructional support on research and writing.

Review and adjust: Use student feedback, reflections, and peer review to ensure assessments are effective.

Want to look at an example?

Check out this example of an authentic assessment that is well-aligned to course learning outcomes. This example is of an Assistive Technology Implementation Assignment and was contributed by Megan McFarland, adjunct professor in Portland State’s College of Education.

Resources for aligning assessments

3. Use a variety of assessment types

Assessment variety includes differences in purpose, cognitive demand, deliverable, and format.

Include both formative and summative assessments:

- Formative assessments: Use low-stakes quizzes, draft submissions, or in-class activities to provide ongoing feedback. These help identify and address learning gaps before final assessments.

- Summative assessments: Use exams, final projects, or presentations to evaluate students’ mastery of course content.

Vary cognitive demands: Balance assessments across Bloom’s levels of complexity. For example:

- Lower level: Multiple-choice quizzes for “Remembering” and “Understanding.”

- Higher level: Essays or case studies for “Analyzing” and “Evaluating.”

Use authentic assessments: Design assignments that simulate real-world tasks, such as conducting interviews, solving case studies, or creating portfolios, to promote deeper engagement.

Diversify formats: Incorporate a mix of traditional (e.g., essays, tests) and creative (e.g., multimedia presentations, group projects) assessments to cater to different learning styles.

Assessment type examples

These PSU examples show varied formative and summative assessments across different course contexts.

More on assessment types

4. Incorporate effective rubrics

Effective rubrics help communicate clear expectations and highlight the most important criteria for success.

Create rubrics for major assignments: Include specific criteria for each component of an assignment.

- For example, a research paper rubric could include categories like “Thesis Statement,” “Evidence Integration,” and “Organization.”

Use descriptive performance levels: Clearly describe what constitutes excellent, good, fair, or poor performance for each criterion.

- Instead of: “Needs improvement”

- Use: “Evidence is cited with proper formatting and integrated into the analysis.”

Provide rubrics in advance: Sharing rubrics when you assign a task helps clarify expectations.

Involve students: Allow students to contribute to rubric design, fostering transparency and ownership. For example, hold a class discussion to identify what constitutes good performance on a group project.

Use rubrics for feedback: Highlight specific areas where students excel or need improvement. This makes feedback actionable and encourages student growth.

Resources for incorporating rubrics

5. Analyze and apply assessment data

Use assessment data to identify learning patterns and make adjustments, both during the term and in future terms.

Collect and organize data: Gather results from both formative and summative assessments. Use tools like gradebooks, surveys, or spreadsheets to track performance trends.

Identify patterns and gaps: Analyze results to determine which outcomes students struggled with. For instance, if most students performed poorly on a research paper’s “Evidence Integration” criterion, review whether the course sufficiently taught this skill.

Adjust instruction:

- Revisit difficult topics

- Add practice opportunities

- Rebalance assessment weights if needed

Refine course design: For example, if students consistently underperform on oral presentations, consider adding a formative practice round with peer feedback before the final presentation.

Communicate changes: Let students know how their feedback or performance has shaped your course.

More on analyzing and applying assessment data

6. Foster a culture of reflection

Reflection helps you and your students close the learning loop and build metacognitive skills that deepen insight and growth.

Incorporate reflection assignments: After major assessments, ask questions such as:

- What was challenging?

- What strategies did you use?

- How might you improve?

Model reflection as an instructor: Share your own reflections on teaching practices and how you adapt based on assessment results.

- For example, “I noticed the class struggled with concept X, so I will include more examples next term.”

Use reflection for metacognition: Encourage students to analyze their strengths and weaknesses.

- For example, have them identify which study strategies worked best for their midterm exam preparation.

Provide feedback on reflections: Highlight meaningful insights in students’ reflections and suggest actionable next steps.

Create a safe environment for reflection: Reassure students that reflections are low-stakes and growth-focused. Avoid grading reflections rigorously.

Resources for analyzing and applying assessment data

Examples of quality assessment design practices

Fink, L. D. (2013). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college courses (Revised and updated ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (2nd ed.). ASCD.

You might also like

👋Need more help?

Submit a support request through our Faculty Support portal for assistance.

Manage breakout rooms

Manage breakout rooms

Note: You can also Pre-Assign Participants to Rooms.

Breakout room basics

- You must have breakout rooms enabled on your Zoom account settings to start breakout rooms. This setting is enabled by default for PSU users. You can adjust your personal account settings through the Zoom web portal at pdx.zoom.us

- You must be the meeting host and use the Zoom client to start breakout rooms.

- You can have up to 50 breakout rooms per meeting and up to 200 participants total in breakout rooms.

- Hosts can move from breakout room to breakout room and send messages to all rooms.

- Participants can request help from a host while in a breakout room with the Ask for Help button.

- Participants who joined the meeting through a web browser are not able to join breakout rooms. As a workaround, those participants can use the main meeting room as their breakout session space.

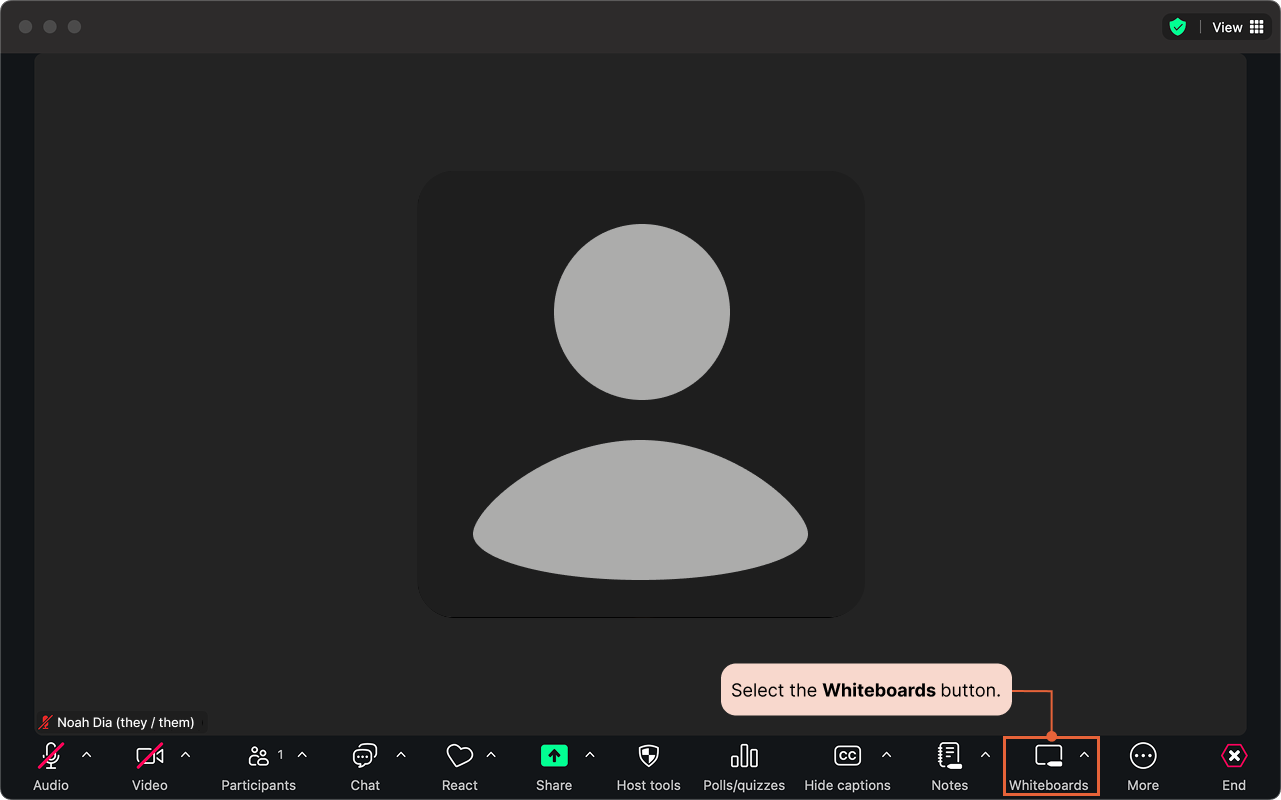

Create breakout rooms during a meeting

- Start the meeting.

- Click Breakout Rooms in the meeting host controls to access the breakout rooms you created.

- Select the number of rooms you would like to create and how you would like to assign your participants to those rooms:

Automatically: Let Zoom split your participants up evenly into each of the rooms.

Manually: Choose which participants you would like in each room. - Click Create breakout rooms.

- Click Options to view and select additional options.

- Click Open all Rooms to send participants to assigned breakout rooms.

Learn more about managing breakout rooms.

This article was last updated Jul 10, 2025 @ 10:28 am.

Permissions overview and sharing media

Permissions overview and sharing media

Media Permission Levels

- Private: Private media is viewable in your account only. No other account can see a private video.

- Unlisted: An unlisted video is viewable by anyone with the direct link. This is the recommended setting for sharing videos with your students.

- Published: If you have a situation where you need to set very specific access to a video, you can create a channel, and publish a video to that channel. If, for example, you want to share a video with a select group of students, but don’t want any one else to see it, you can use a channel.

To share media access with others, you need to change the default Private setting to Unlisted. Instructions are in this Share Media Via URL tutorial.

Channel Membership Roles

- Channel Owner: The channel owner is the person who created the channel. Only the owner can delete the channel.

- Channel Manager: A channel manager can view channel content, add media to the channel, moderate channel content, and manage users.

- Channel Moderator: A channel moderator can view channel content, add media to the channel, and moderate channel content.

- Channel Contributor: A channel contributor can view channel content and add media to the channel.

- Channel Member: A member can view the channel content.

Channel Types

- Private Channel: media in a Private channel can only be viewed or modified by by channel members.

- Restricted Channel: media in a Restricted channel is viewable by any PSU user. The channel can be accessed via URL or by searching in MediaSpace. Only users who are invited to join a Restricted channel can add to or edit its media.

Share media via URL

- Log into media.pdx.edu

- Click the button with your name on it in the upper right corner, and click My Media.

- Find your video in the list, and click on it.

- Find the Actions button in the lower right.

- Click the + Publish option in the list. See permissions options above.

- To share media, make sure it’s set to Unlisted.

- Click Save.

- Click the Share button below the video.

- On the Link to Media Page tab, copy the web address.

This article was last updated Jun 13, 2025 @ 2:25 pm.

Zoom Whiteboard in Canvas

- Home

- Articles Posted by

Zoom Whiteboard in Canvas

This article was last updated Jul 10, 2025 @ 10:29 am.

Why would I use Zoom Whiteboard?

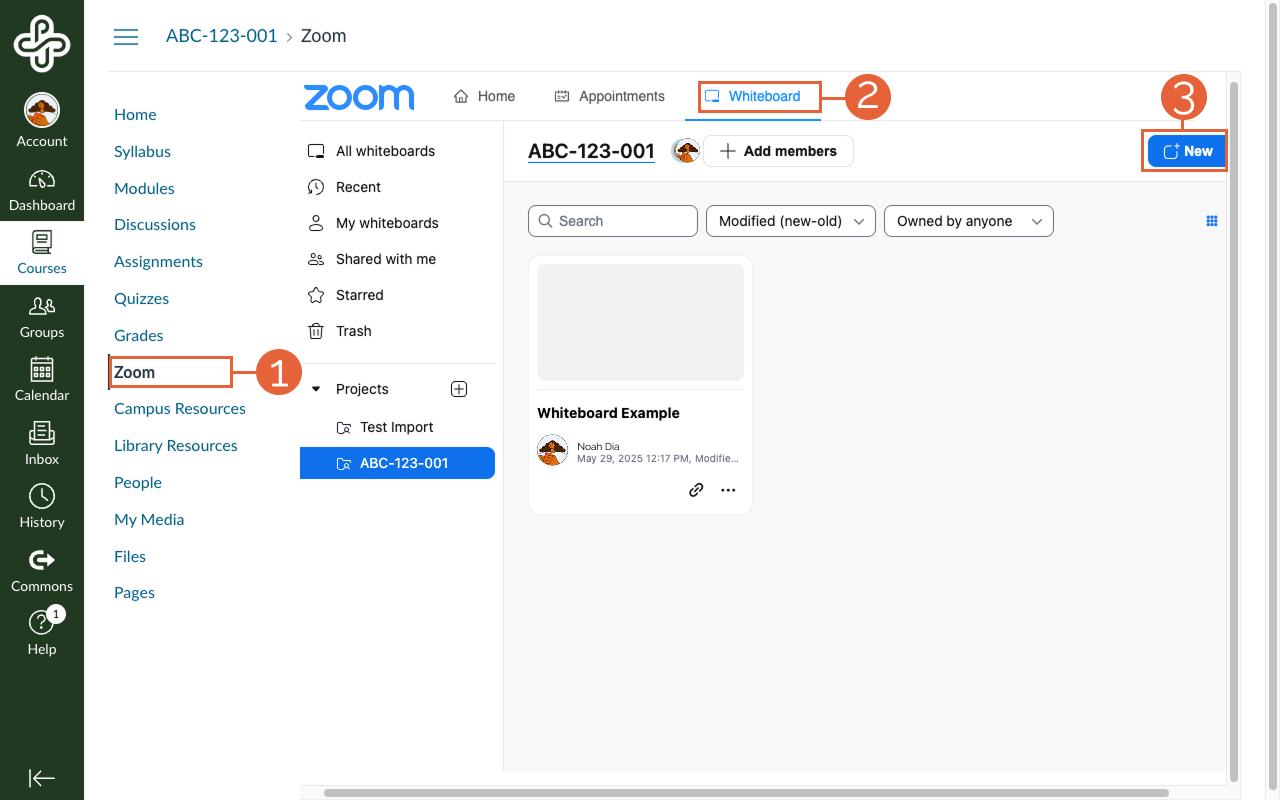

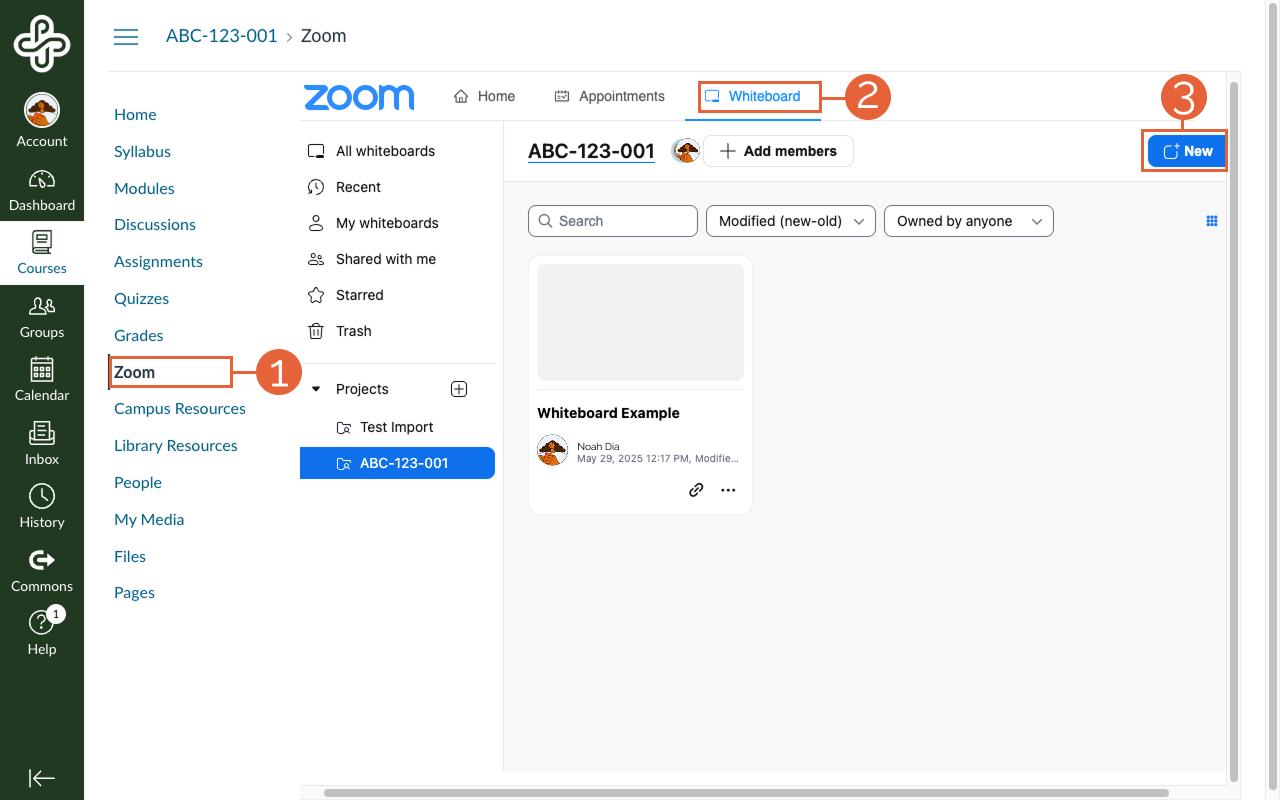

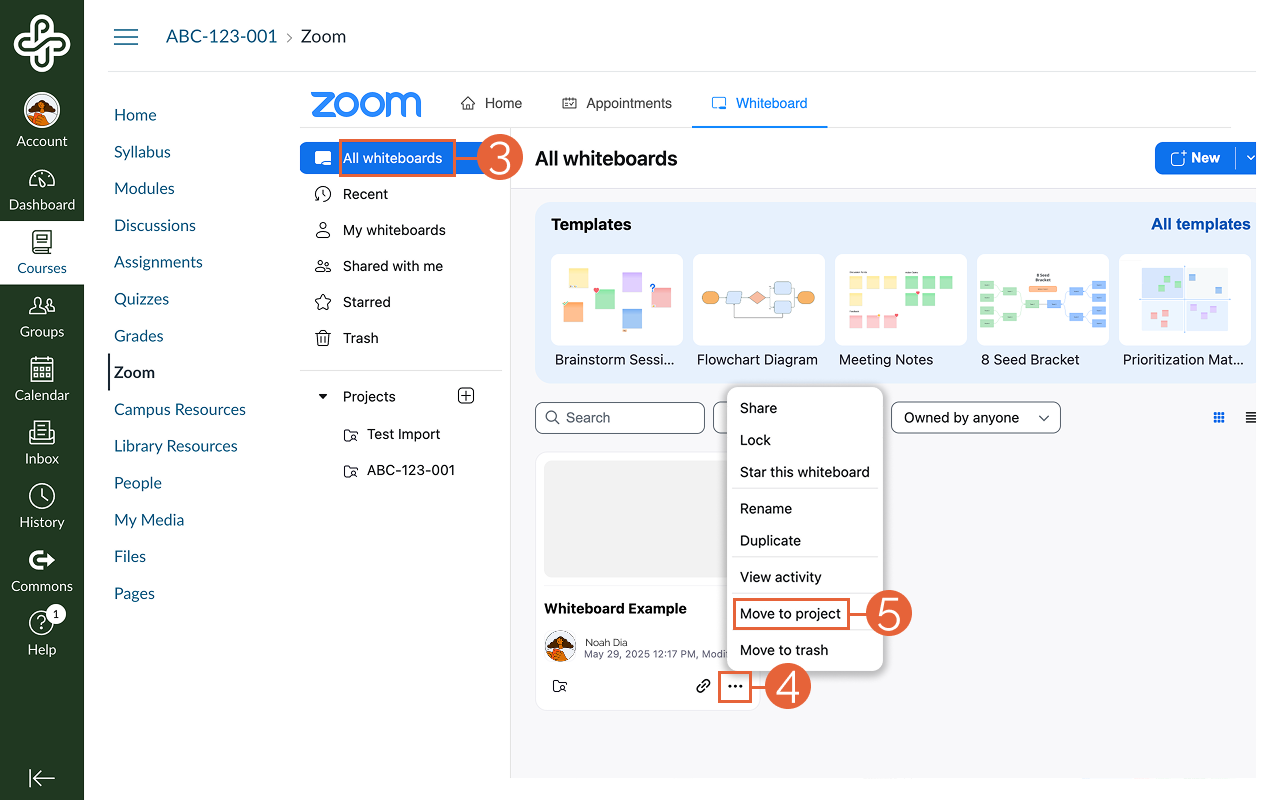

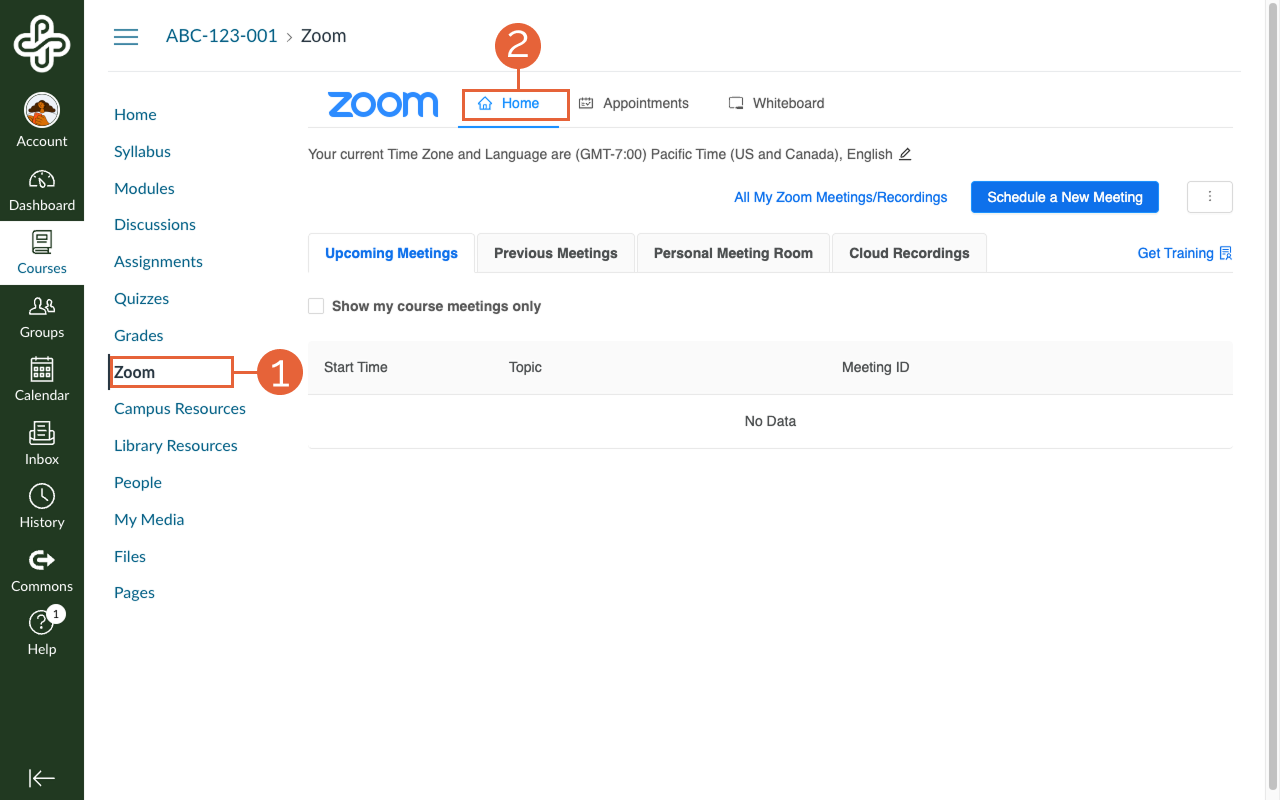

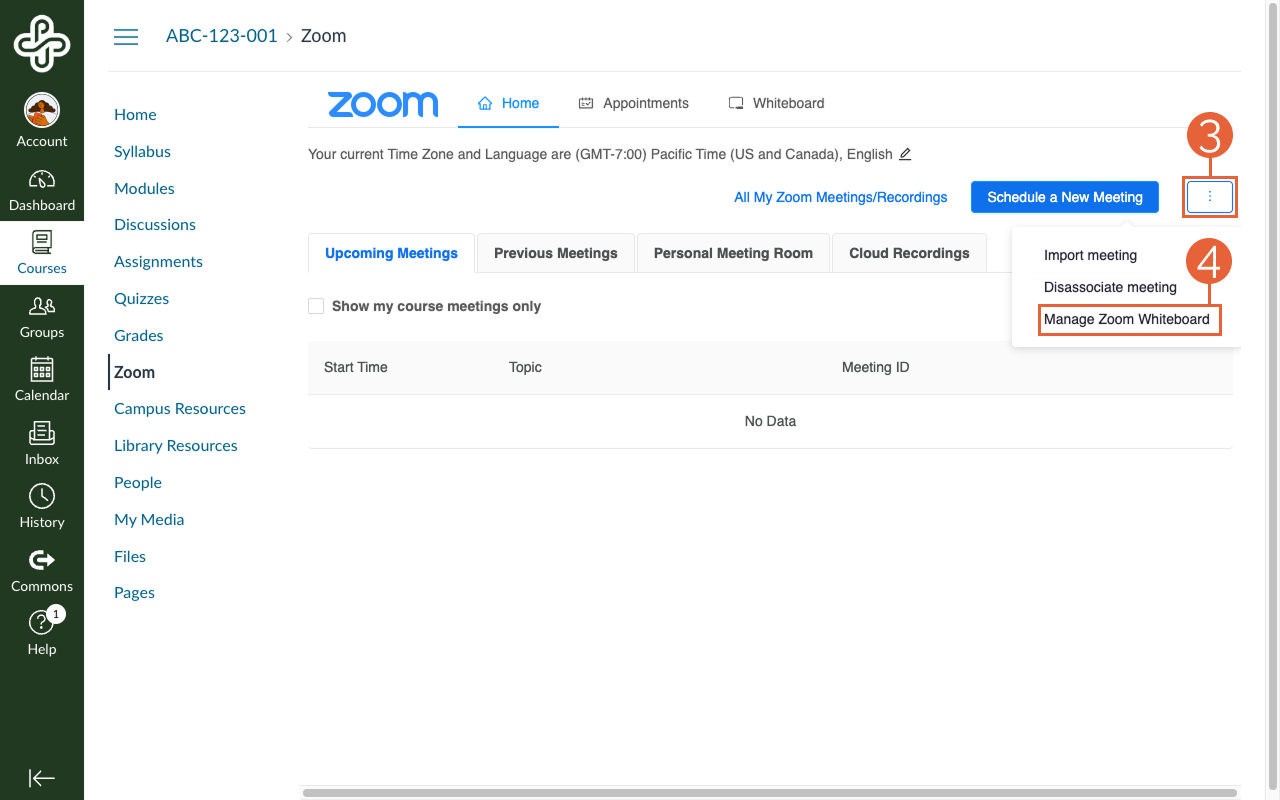

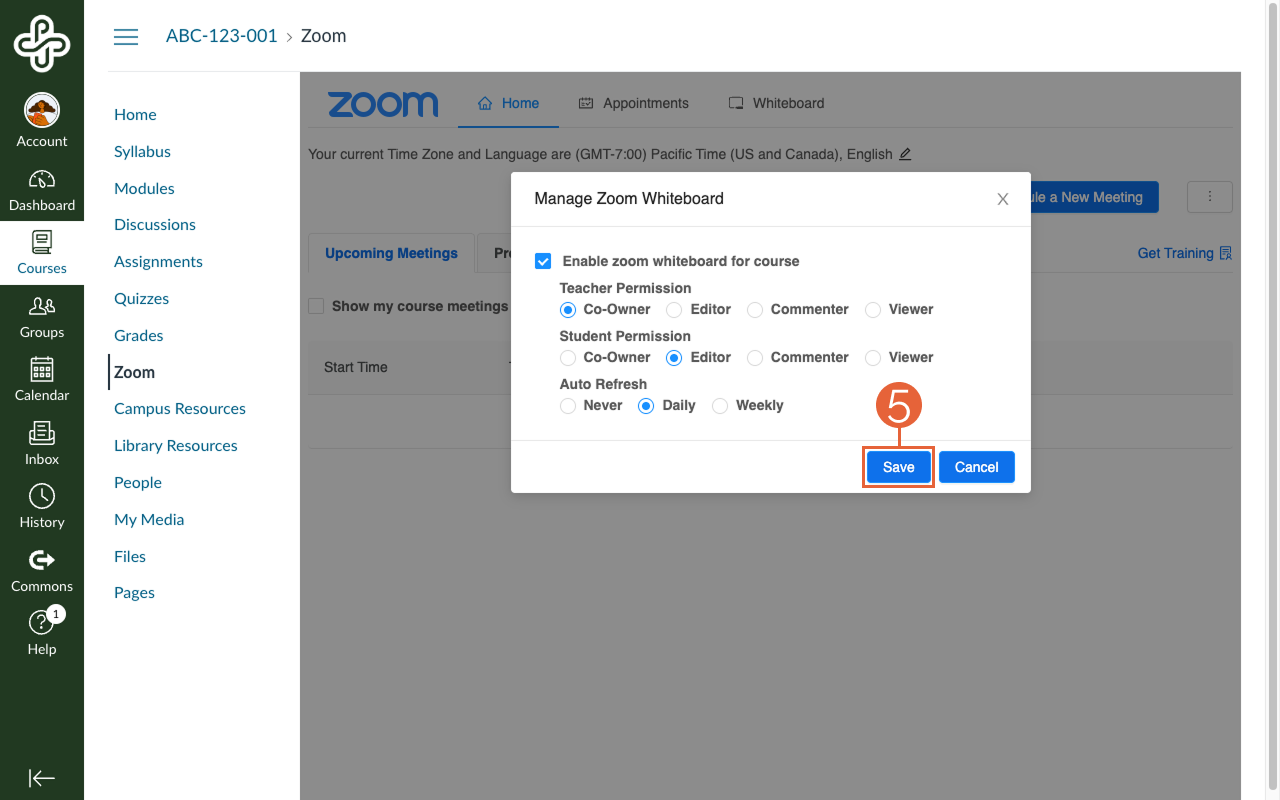

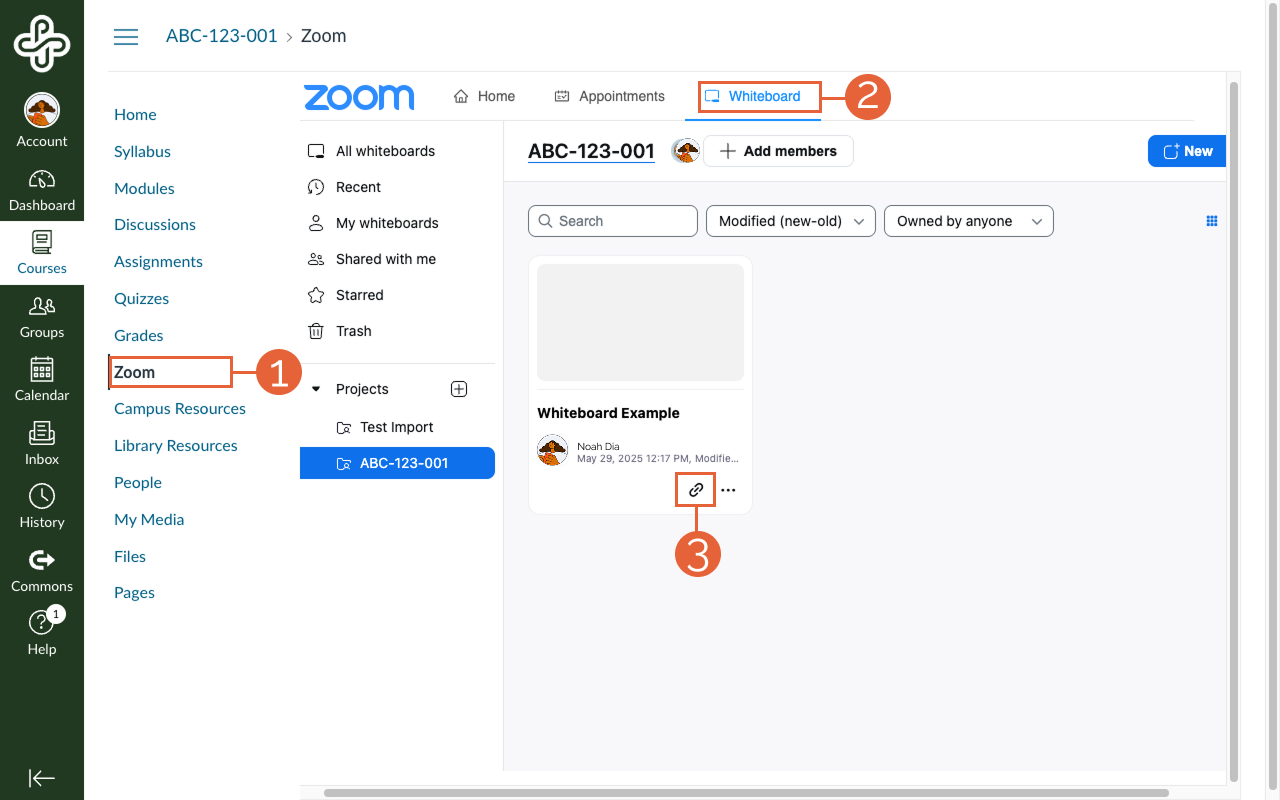

Zoom Whiteboard is a virtual tool for visual collaboration. It enhances meetings by allowing instructors and students to brainstorm, annotate, and organize ideas together. It’s useful for interactive discussions, problem-solving, and concept mapping. Zoom Whiteboards also support asynchronous engagement, enabling ongoing collaboration, group work, or reflection outside of class time.