Designing your course

A comprehensive guide to course design at Portland State

Contributors:Misty Hamideh, Andrew F. Lawrence, Lindsay Murphy

This article is an introduction to planning your course using backwards course design. It will guide you in using observable, measurable outcomes to design clear and engaging learning experiences. You can use the included strategies both for revising an existing course or designing a new one.

This guide describes a range of course design or revision techniques. You might use the Rule of 2’s: Simple course design template to make notes and capture ideas as you work through this article. This article and the Rule of 2’s template follow a backward design process, where you start planning with student learning outcomes in mind (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005).

This guide describes a range of course design or revision techniques. You might use the Rule of 2’s: Simple course design template to make notes and capture ideas as you work through this article. This article and the Rule of 2’s template follow a backward design process, where you start planning with student learning outcomes in mind (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005).

What is course design?

Course design, sometimes called curriculum design or course development, is a structured process of planning and organizing the elements of a course to achieve specific learning outcomes. A course design process typically includes setting clear objectives, structuring content, selecting appropriate teaching methods, aligning assessments, and ensuring that the course meets the needs of diverse learners. Whether for in-person, online, or hybrid environments, course design aims to create a cohesive, student-centered learning journey that facilitates understanding and application of knowledge.

From a Student’s View

A student shares what it felt like to navigate a well-organized course — and why it mattered:

“Organization of courses can be the ultimate decider if a student with ADHD/Autism passes. In a school year, I like to do a combination of online and in-person learning. I’ve seen the issue of course organization cross to both of these settings. [In one course,] the writing was in a small, smashed-together font with as much information as possible. There were also large amounts of abbreviations that weren’t intuitive. I found myself falling behind quickly before having to develop my own system to decipher the calendar. This led me to putting more energy on this then setting myself up for success in the course.”

- Lio, Portland State undergraduate student

From a Student’s View

A student shares what it felt like to navigate a well-organized course — and why it mattered:

“Organization of courses can be the ultimate decider if a student with ADHD/Autism passes. In a school year, I like to do a combination of online and in-person learning. I’ve seen the issue of course organization cross to both of these settings. [In one course,] the writing was in a small, smashed-together font with as much information as possible. There were also large amounts of abbreviations that weren’t intuitive. I found myself falling behind quickly before having to develop my own system to decipher the calendar. This led me to putting more energy on this then setting myself up for success in the course.”

- Lio, Portland State undergraduate student

Why is good course design important?

Thoughtful course design is critical for effective teaching and meaningful student learning. Just as an instruction manual guides someone through assembling a complex item, a well-designed course with clear course goals will guide students through the learning process, ensuring that each step builds toward a comprehensive understanding of the topic. A well-designed course fosters engagement, accommodates diverse learning styles, and removes unnecessary barriers to understanding. It also improves instructor effectiveness by providing a clear roadmap for teaching and assessment.

Effective course design contributes to:

- Clarity and Accessibility: Students can easily understand course expectations, objectives, and how to navigate materials.

- Engagement: Thoughtful design encourages active participation, fostering a deeper connection to the subject matter.

- Equity: By considering diverse learner needs, good design ensures inclusivity, making content accessible to everyone.

- Alignment: Ensuring that learning objectives, activities, and assessments are in harmony increases the likelihood of achieving desired educational goals.

- Efficiency: A structured course reduces redundancies, saving time for both instructors and students.

How do I design an effective course?

Designing a course that engages students and supports meaningful learning requires more than just assembling materials. It involves intentional planning—starting with clear goals, building aligned assessments, designing active learning experiences, and maintaining a consistent structure. These strategies will help you build a thoughtful, student-centered course that meets your instructional goals and fosters student success.

1. Identify course goals

You may be familiar with student learning outcomes, also sometimes called learning objectives or course goals. Your course may have preset outcomes, or you might need to identify outcomes. In either case, you need to have observable and measurable, so you can clearly communicate how you will observe student work and measure whether it meets the goals of the course. Outcomes might address content knowledge, skills, or even dispositions that you intend students to acquire and should help them focus their learning and attention and connect the dots between course content, learning activities, and assessments.

Imagine that a large box arrives at your house. It’s full of parts to assemble but has no instructions and no pictures of the final object. This is how students often feel when they enter a course without student learning outcomes or clear goals.

Once you’ve identified the outcomes for your course, they form the foundation, blueprint, or roadmap that everyone in the course is working toward. As you design or revise your course, keep coming back to these outcomes to ensure your planned assessments, assignments, learning activities, and teaching strategies align with your intended learning outcomes.

2. Build assessments around course goals

Think back to that mysterious box that arrived at your house. What if the box had instructions, but they didn’t match the parts? What if parts were missing or the instructions skipped big steps? This is analogous to what happens when assigned work doesn’t align with the course goals or when assessments don’t match what has been taught in the class. It’s difficult for students to understand why the work is necessary or relevant or how their assessments reflect what they are learning.

Consider the purpose of each of your assessments.

- Do they help you and your students perceive how much progress you’ve all made toward the course goals?

- Are they being used to measure whether students are ready to move onto the next stage?

- Should they be graded or used for practice to help students focus on specific topics?

It can also be helpful to give students opportunities for peer review, self-reflection, and suggestions rather than a letter or number grade. Research shows that grades are often demotivating for students and can be confusing when students try to improve their grade in future assignments. While we often look at grades as inevitable and ubiquitous, they are relatively new as a standard practice in higher education (Schinske & Tanner, 2014).

This section provides a brief overview of assessments as they relate to course design. The terms “assessments” and “assignments” are used interchangeably here to describe ways to externalize student learning and better observe and measure it. For a more in-depth discussion of assessments and guidance on building assessments around course goals, please review the [ASSESSMENT PILLAR] article.

Understanding Assessment Methods

Explore various assessment methods and tools for effective teaching.

3. Design learning experiences and plan teaching strategies

One of the most common mistakes in course design is assuming the material is the course. Rather, the material is merely one tool of the course. The learning experiences, relationships, and teaching strategies you plan should align with your course goals and students’ needs. “Those who do the work do the learning” (Doyle, 2011) — so the more students have opportunities to interact with the course materials, their peers, and you, the better. When considering what activities to design for your course, ask yourself what students can do to connect with the course skills, dispositions, and concepts.

There is a wide range of teaching and learning approaches to consider:

- Active learning provides experiences that give students more active involvement in learning about and evaluating perspectives.

- Flexible teaching strategies emphasize teaching and learning across course modalities (online, in-person, or blended)

- Community-engaged learning invites students and community members to participate in mutually beneficial goals and projects in well-planned and structured partnerships

- Open education focuses on using free learning materials that allow students to co-create alongside their instructors, building non-disposable assignments, and encouraging agency

- Universal Design for Learning emphasizes student choice, access, and agency in assignment and course design to reduce/eliminate barriers to learning

More about teaching strategies

More about online course design

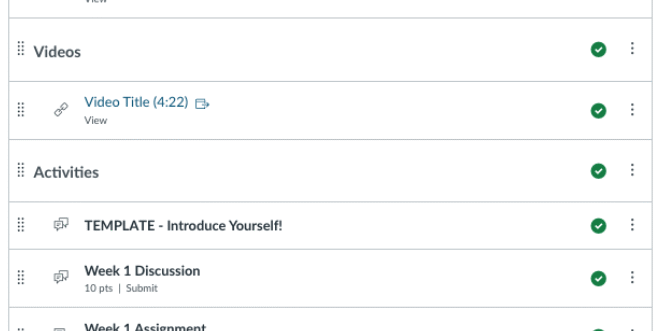

4. Build a clear course structure

Once you have identified your course goals and designed your assessments and learning experiences to align with these goals, you’ll need to consider how to present this information to your students. Regardless of the modality of the course, a clear and consistent structure will help reduce students’ anxiety, enhance focus on learning, and promote better engagement with course materials, ultimately supporting academic success.

Using Canvas, even for a fully in-person course, can help enhance communication and organization by providing a centralized hub for your course. Canvas can help you:

- distribute materials

- track assignments and student progress

- streamline grading and feedback

- provide a structured learning cycle students can follow.

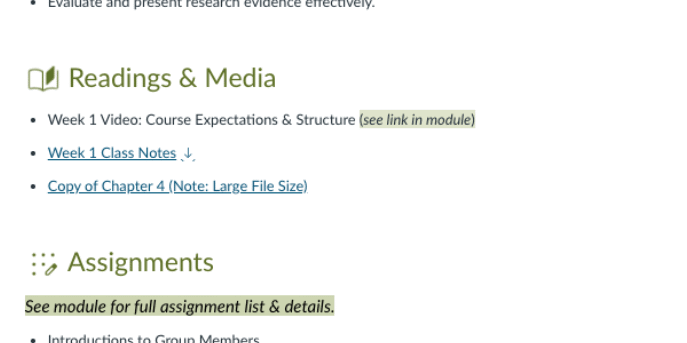

An effective syllabus can also provide a clear course roadmap, outlining learning outcomes, assessments, policies, and support resources, which helps set clear expectations for students. A well-designed syllabus can promote better time management, improve student performance, and create a more organized learning environment.

More about course structure

5. Get student input on your course design

Whether you use feedback from last term’s students or suggestions from this term’s students, inviting your students to give design input will do a lot to help the course run smoothly.

- Student input encourages student motivation, participation, and agency.

- Course co-creation helps to meet student needs by encouraging a diversity of ideas and choices.

Ways to encourage student input as you plan the course

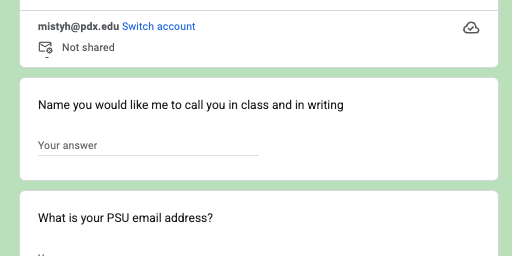

Ask: Send out a poll about a week before the course begins to ask about technology access, communication mode preferences, and assignment type feedback. Students might be most interested in devoting some class time to asking questions while working on video projects rather than term papers, but as instructors, we won’t know that unless we ask.

Brainstorm: Give students three or four learning outcomes on the first day, and ask the class to brainstorm other outcomes they would like to include on the list. Work to include one or two of their suggestions on the final list of student learning outcomes.

Offer: Offer choice in how students complete some assignments. This might mean a choice of assignment formats, collaborations, or due dates.

Negotiate: Create a negotiated syllabus with your students during the first week of class. Give them a say in the course goals, assessments, assignments, and activities. You don’t have to make everything negotiable. A critical part of planning is to identify the scope of choice. This is a great way to build community and get student buy-in around course requirements. “The Negotiated model is totally different from other syllabuses in that it allows full learner participation in selection of content, mode of working, route of working, assessment, and so on. It should by this means embody the central principle that the learner’s needs are of paramount importance” (Clarke, 1991).

Want to try a pre-term survey?

Check out this sample pre-term survey to get ideas for the kind of questions you may want to ask your students. Then, use the link at the top of the form to make your own copy and modify it to fit your class needs!

Never used Google Forms before (or need a refresher)? Visit the Google Forms Support page for help getting started!

Resources on getting student input on course design

Clarke, D. F. (1991). The negotiated syllabus: What is it and how is it likely to work? Applied Linguistics, 12(1), 13–28.

Doyle, T. (2011). Learner-centered teaching: Putting the research on learning into practice. Stylus.

Schinske, J., & Tanner, K. (2014). Teaching more by grading less (or differently). CBE—Life Sciences Education, 13(2), 159–166.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (2nd ed.). ASCD.

You might also like

👋Need more help?

Submit a support request through our Faculty Support portal for assistance.