Customize course dates and participation settings in Canvas

Customize course dates and participation settings in Canvas

This article was last updated May 19, 2025 @ 2:34 pm.

An important feature in Canvas is setting and adjusting course participation dates. Course participation dates control when students can access a course. This guide will help you understand how course participation dates work and how to change them if needed.

How do Course Participation Dates work in Canvas?

Course participation dates in Canvas determine when a course is accessible to students. There are two types of participation you can choose from:

- Term Participation: This type of participation makes a published course accessible during default dates automatically set by PSU for all courses in the specific academic term selected. These dates are not customizable. (Note: Term dates are only applied to courses that are CRN-bearing.)

- Course Participation: These participation dates are customizable and allow you to give students early access or extend access beyond the term dates. For example, if you want students to review materials before the official start of the term, you can set an earlier start date.

Whether you choose Term or Course participation, the Start date displayed is the first day students can access the course, while the End date is the last day students can access the course. After this date, students can no longer access the course materials or assignments.

Frequently Asked Questions

What if I choose course participation and don't set the dates?

If you don’t set course dates, the term dates will be used instead.

Can I set dates for specific sections of my course?

Section dates cannot be edited by instructors. sections can be created for specific situations, like providing alternative access for students who need to resolve an incomplete, but you will need assistance from an OAI staff member to create the section and set the dates. More information about this can be found in the Incomplete Student Access to a Canvas Course article.

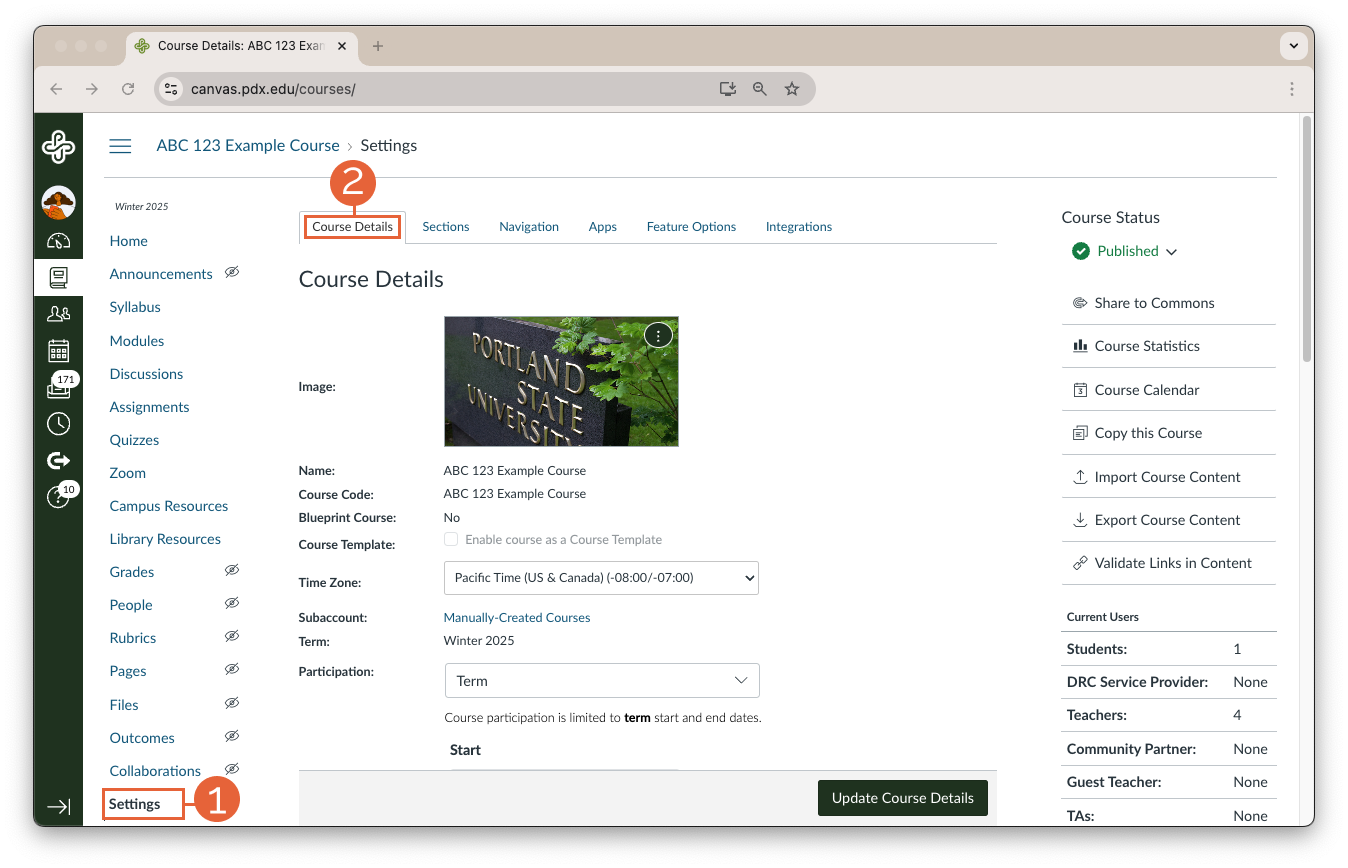

How do I change Course Dates in Canvas?

1. Select the course you want to edit from your Canvas dashboard

2. Navigate to Course Settings

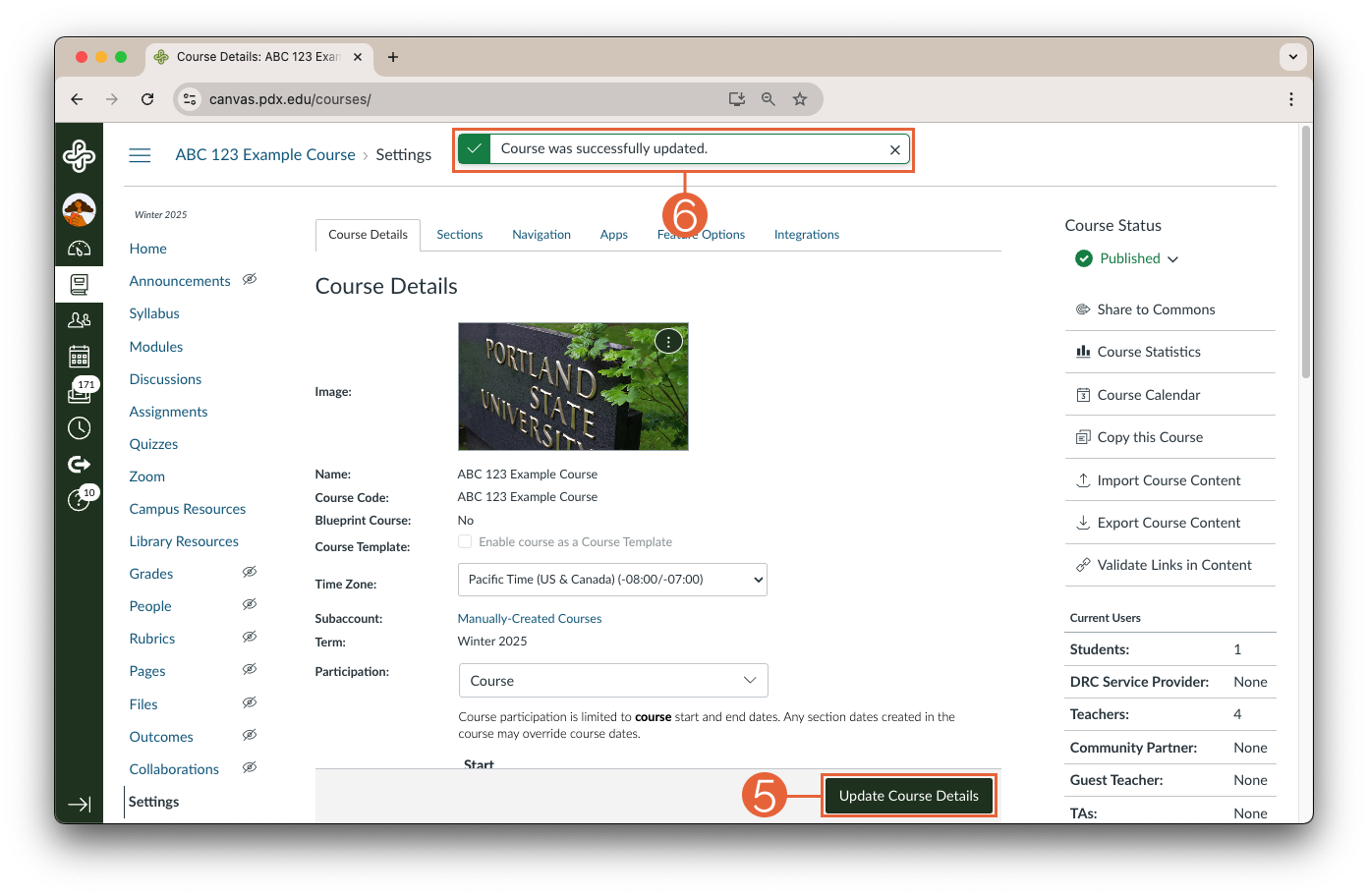

- Scroll down the course navigation menu on the left side and click on Settings (1) and select the Course Details (2) tab.

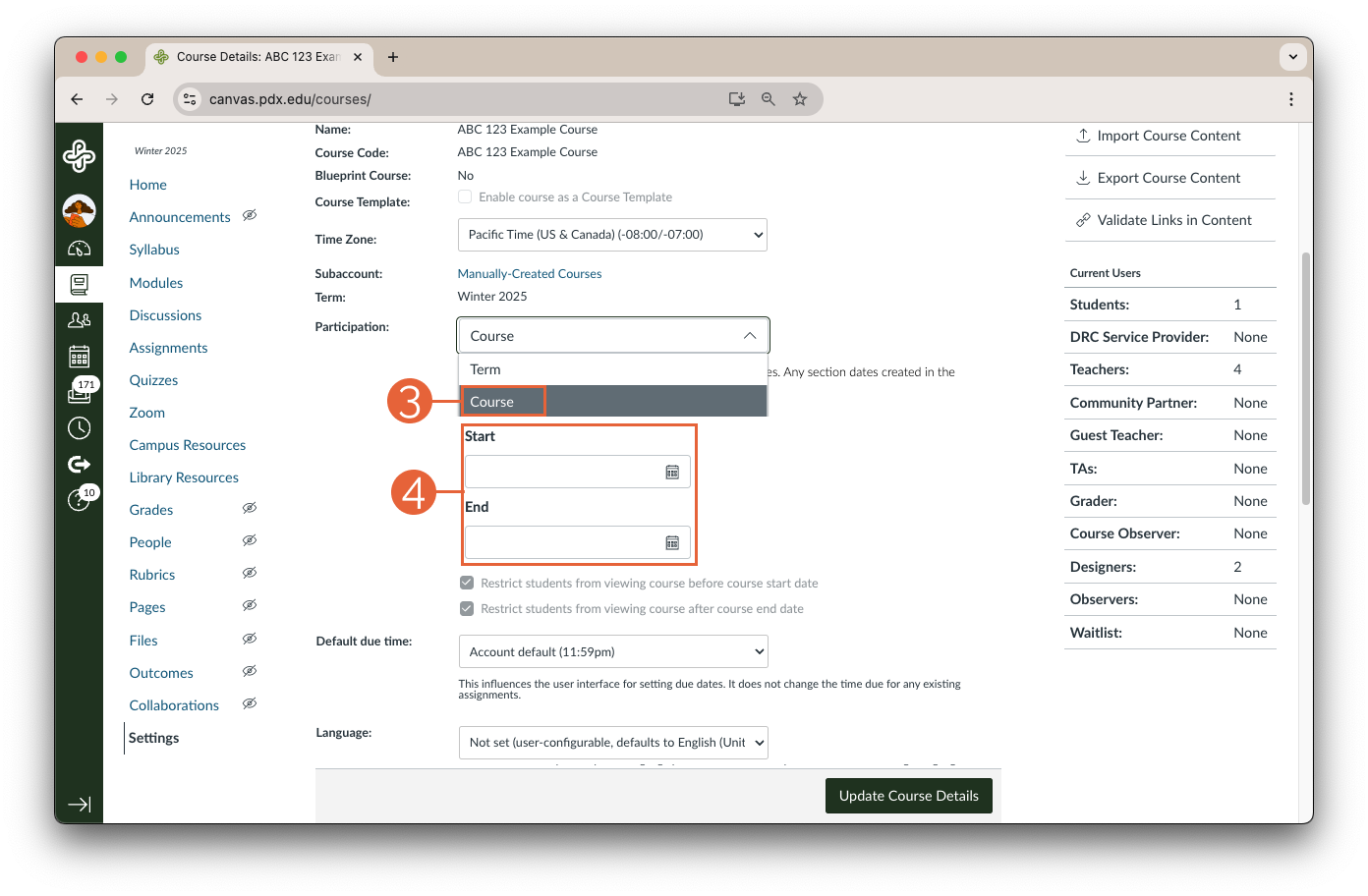

3. Update Custom Course Participation Dates

- Change the Participation drop-down to Course (3).

- Enter the desired Start and End Dates (4) for your course. Make sure the dates align with your teaching plan.

Note: Both start and end dates must be entered or Term dates will remain in effect.

4. Save Your Changes

- Scroll to the bottom of the page and click Update Course Details (5).

- A message will appear at the top of the page confirming that you have successfully made the update (6).

Best Practices for Course Participation Dates

- Communicate with Students: If you set custom dates, let your students know when the course will open and close. You can email all students registered in your course using Google Groups beginning approximately two weeks before the start of the term!

- Allow Review Time: Consider extending the course end date by a few days to let students review their grades and course materials.

Setting and adjusting course participation dates in Canvas helps you manage your course effectively and gives students the access they need to succeed. With these steps, you’re ready to make any necessary changes with confidence.

Community engagement toolkit

Community engagement toolkit

Resource type: Google site and Digital Guidebook

Intended for: New faculty, emerging practitioners, seasoned educators, students

Contributors: Created by PSU staff, graduate students, faculty, interviewed students, and community partners

A toolkit for students

The Community Engagement Toolkit is designed to help students develop and practice skills used to engage with their community for social change. The toolkit will help students explore how and why they want to engage within the community, find the tools to make meaningful connections with communities, and build their sense of community agency to become a catalyst for change.

Community-engaged learning, also known as community-based learning or service learning, is a teaching and learning strategy that integrates meaningful community service or engagement with instruction and reflection to strengthen communities and expand the learning experience.

Get started with the faculty and facilitator guide

The Faculty and Facilitator Guide is a simple guide for faculty and facilitators supporting students’ use of the Community Engagement Toolkit. The guide includes learning objectives, sections, and sequencing support for the toolkit’s five modules. The guide also includes ideas for how to integrate resources and activities into your course or workshop as well as additional facilitation and faculty support resources.

What's in the Community Engagement Toolkit?

This module defines community engagement as collaborative work with communities on shared goals, emphasizing personal reflection, understanding issues, and making impactful contributions in various forms of social change.

You will explore three sub-topics:

- Finding your issue

- Determining your impact

- The continuum of social change

Module Two helps individuals identify their skills and capacities for community engagement, explore various opportunities that align with their values, navigate the communication process with potential partners, and overcome initial anxiety and imposter syndrome to foster meaningful connections.

You will explore four sub-topics:

- Determining your how

- Finding your where

- Starting communication

- Overcoming anxiety

This module emphasizes the importance of ethical community engagement by exploring how identities, positionality, and worldview influence interactions, highlighting the need for awareness of these factors to prevent harm and promote authentic relationships, power redistribution, and social change.

You will explore two sub-topics:

- Understanding ethics, positionality, and worldview

- Applying ethical community engagement principles

Module Four highlights that effective and sustainable community engagement demands preparation, reliable communication, reciprocal relationships, and cultural sensitivity along with feedback and graceful transitions to ensure meaningful impact for all involved.

You will explore four sub-topics:

- Preparing yourself to engage effectively

- Navigating engagement with your community partner

- Giving and receiving feedback

- What next? Closure and next steps

Engaging others in community work amplifies impact but requires careful planning to ensure ethical participation; this section offers guidance on connecting with like-minded individuals and organizing accessible events.

You will explore two sub-topics:

- Connecting with others

- Organizing community engagement events

Understanding Threaded Canvas Discussions

Understanding Threaded Canvas Discussions

This article was last reviewed May 9, 2025 @ 4:18 pm.

In Canvas Discussions, a “thread” is a conversation that starts with an initial post and includes all the replies to that post. Think of it as a single topic of conversation and all the responses related to it. This structure helps keep Discussions organized, so it’s easier for readers to follow along with specific topics or questions.

By default in Canvas Discussions, only the first reply each student submits to your initial topic is visible when you first open a Discussion. To see all replies and ongoing conversations within each thread, you need to click the “Expand Threads” button. This action will display all the replies associated with each initial response.

How to navigate the Expand Threads feature

- Open the Discussion: Navigate to the course discussion page as you normally would.

- Locate the Expand Threads Button near the top of the discussion posts.

- Select Expand Threads. By selecting this button, all replies and ongoing conversations will become visible beneath each initial post.

- You can now scroll through all conversations. To reply to a specific post or comment, select the Reply button beneath that post.

Instructor view vs. student view

When you select either Expand Threads or Collapse Threads, this change affects the content of the page you are currently viewing, but it does not affect what students see. Your students will also need to click “Expand Threads” on their end to see all the replies.

The Engaged Teacher Microcredential

The Engaged Teacher Microcredential

Resource type: Microcredential

Intended for: New faculty, emerging practitioners

Contributors: Megan McFarland, Grant Scribner, Kendra Woodstead

The Engaged Teacher: From Concept to Classroom Microcredential offers faculty the opportunity to explore, experiment, and enhance their teaching practices with personalized support.

This 10-hour program encourages participants to delve into teaching ideas sparked by past experiences, new insights, or persistent challenges. Through guided exploration, collaborative consultations, and reflective practice, faculty implement and refine strategies tailored to their disciplines and classrooms. Upon completion, participants earn an OAI Teaching Innovator digital badge and receive recognition as Featured Engaged Teachers in OAI’s monthly newsletter, showcasing their commitment to meaningful teaching innovation.

Microcredential Modules

In this module, explore foundational and specialization resources from PSU’s Office of Academic Innovation to spark ideas, address challenges, and identify new strategies to enhance your teaching practice.

- Discover new teaching strategies and approaches to address challenges, barriers, or curiosities in your classroom.

- Reflect on current practices and identify opportunities for growth and innovation in your teaching.

- Select and share articles that inspire or support your chosen area of focus for implementation.

In this module, expand your knowledge by selecting and exploring an external resource of your choice to deepen understanding of a new teaching strategy or area of interest.

- Identify an external resource that aligns with your chosen teaching strategy or area of interest.

- Gain deeper insights into your selected topic through independent exploration.

- Share evidence of the resource and its relevance to your teaching context in the artifact submission page.

In this module, connect with OAI staff to discuss your area of interest and collaborate on crafting an implementation plan tailored to your teaching goals.

- Engage in a consultation with OAI staff to discuss the chosen teaching strategy or area of interest.

- Collaborate to develop a personalized implementation plan tailored to your teaching goals, using provided templates and examples.

- Submit evidence of correspondence and the completed implementation plan in the artifact submission page.

In this module, implement your new teaching strategy or idea. Put your plan into action to enhance your teaching practice and prepare for reflection.

- Implement a new teaching strategy or idea developed in the previous modules.

- Apply the implementation plan to a real teaching context to explore its impact.

- Prepare to share insights and results from the implementation.

In this module, reflect on your implementation experience and share insights, challenges, and future implications for your teaching practice.

- Reflect on the implementation process, including successes, challenges, and key takeaways.

- Articulate insights gained and their implications for future teaching practices.

- Share a written, audio, or video reflection to document and communicate the experience.

Starting a New Canvas Course

Starting a New Canvas Course

This article was last updated Jan 16, 2025 @ 1:17 pm.

You don’t have to wait for official course shells to be released before building future courses. If you are a Teacher in at least one course, you can create empty course shells for a pressure-free environment to experiment with.

Can I use a course shell I made for teaching?

Empty course shells are different from those released to faculty by your department because they are not connected to a CRN. Any course shell you create will not automatically enroll/unenroll students. For this reason, it is not advised that you use these courses as your active teaching environments.

How do I copy a course I made into the CRN-bearing course shell?

Copying over course content into a CRN-bearing course is quickly accomplished with the Course Import Tool. To learn how to use the Course Import Tool, please review How do I copy content from another Canvas course using the Course Import tool?

What do I need to complete this process?

-

- Stable internet connection

- Computer

- Web browser (Chrome or Firefox work best)

- Your PSU-affiliated Canvas account

- A minimum of one course where you are enrolled as the Teacher

How to create a course shell in Canvas

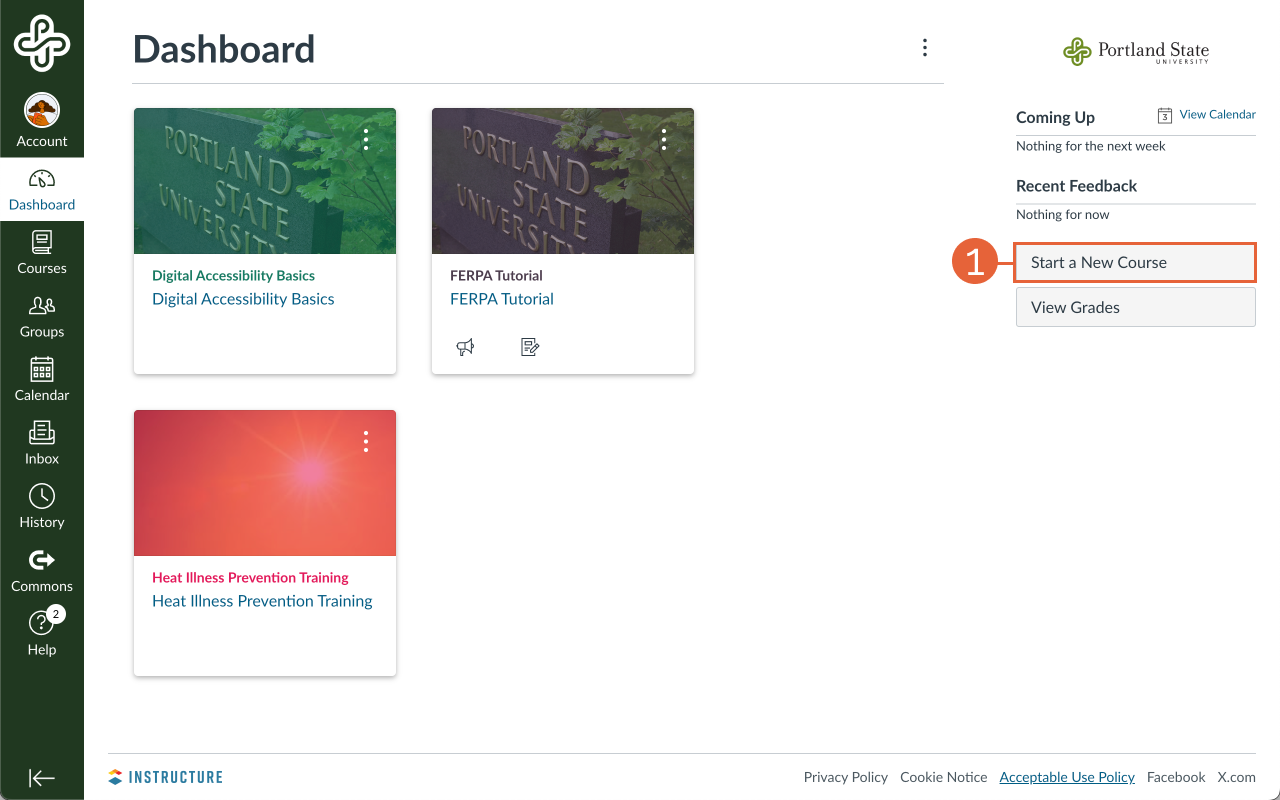

From the Dashboard

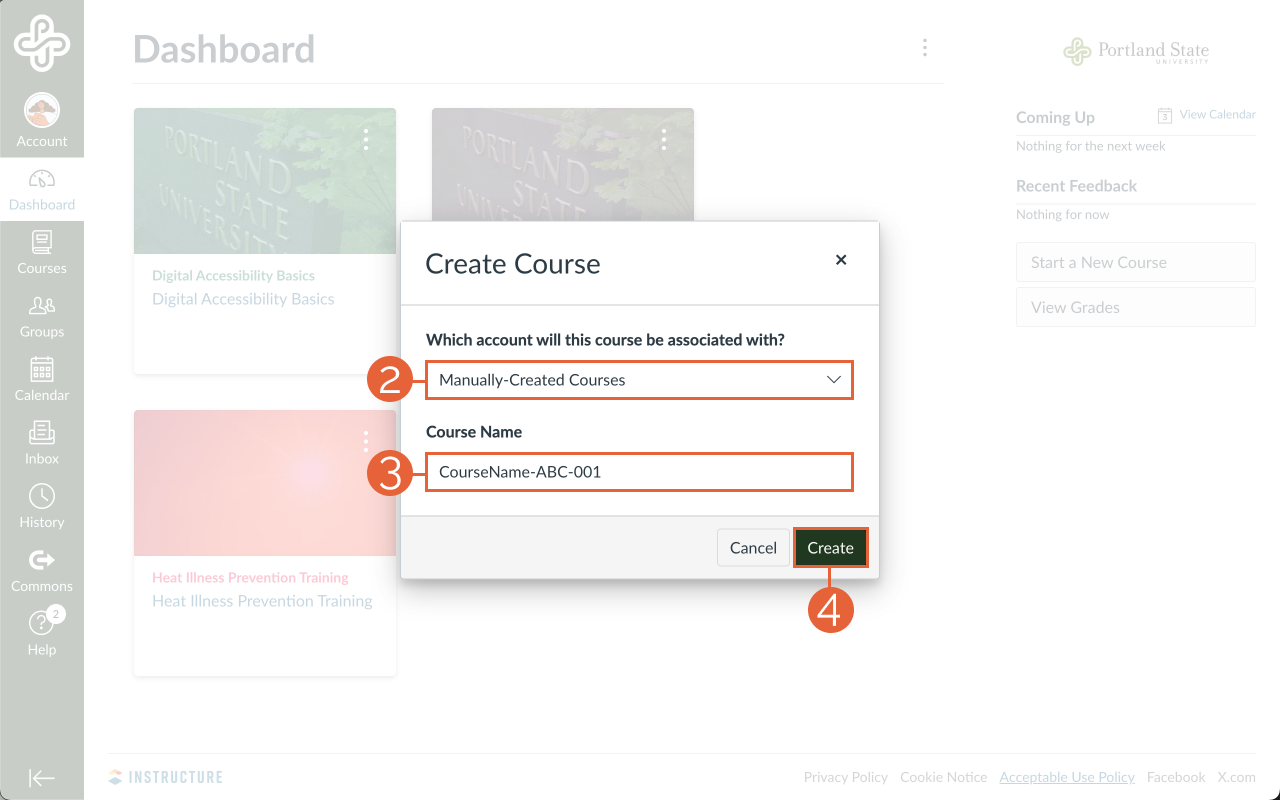

- Select the Start a New Course (1) button on your Canvas Dashboard on the right beneath “Coming Up.”

- Select Manually-Created Courses (2) from the “Which account will this course be associated with?” dropdown menu.

- Enter a name for your new course in the "Course Name" (3) field.

- Select the Create (4) button at the bottom of the page.

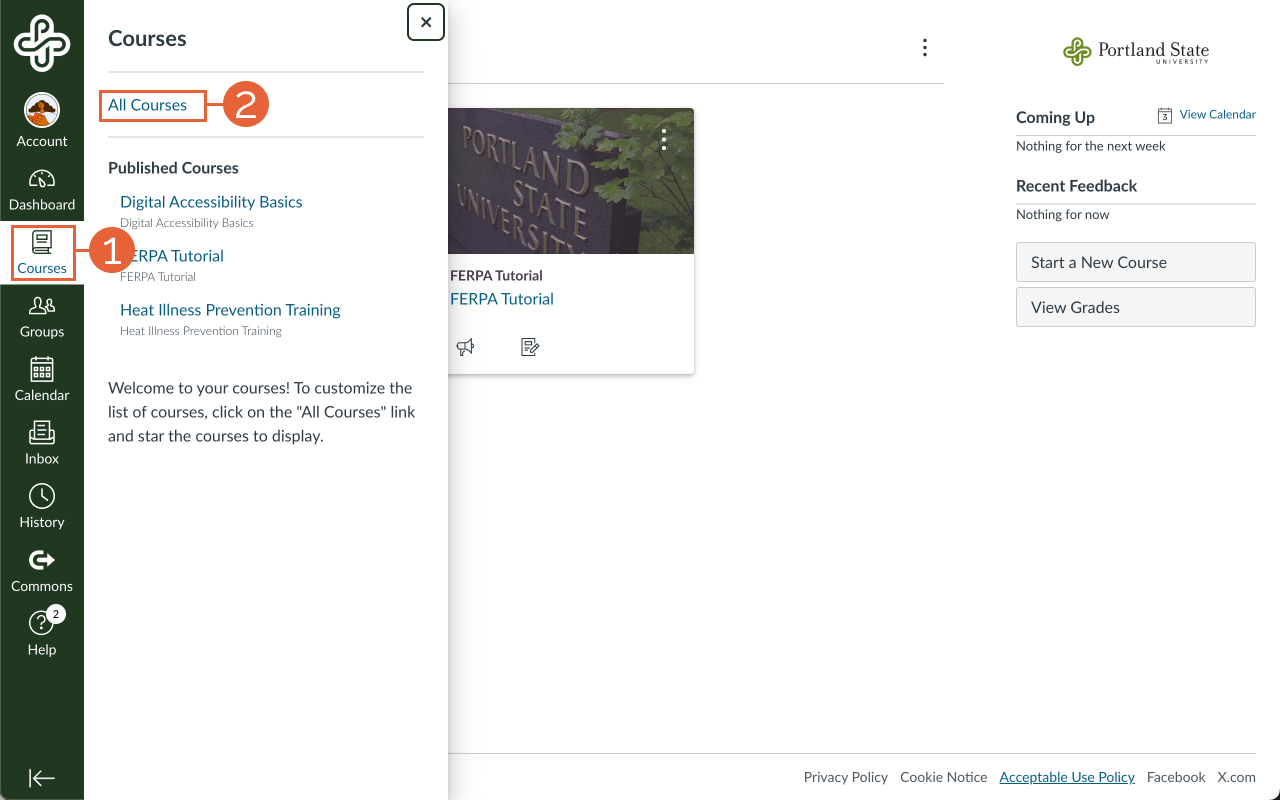

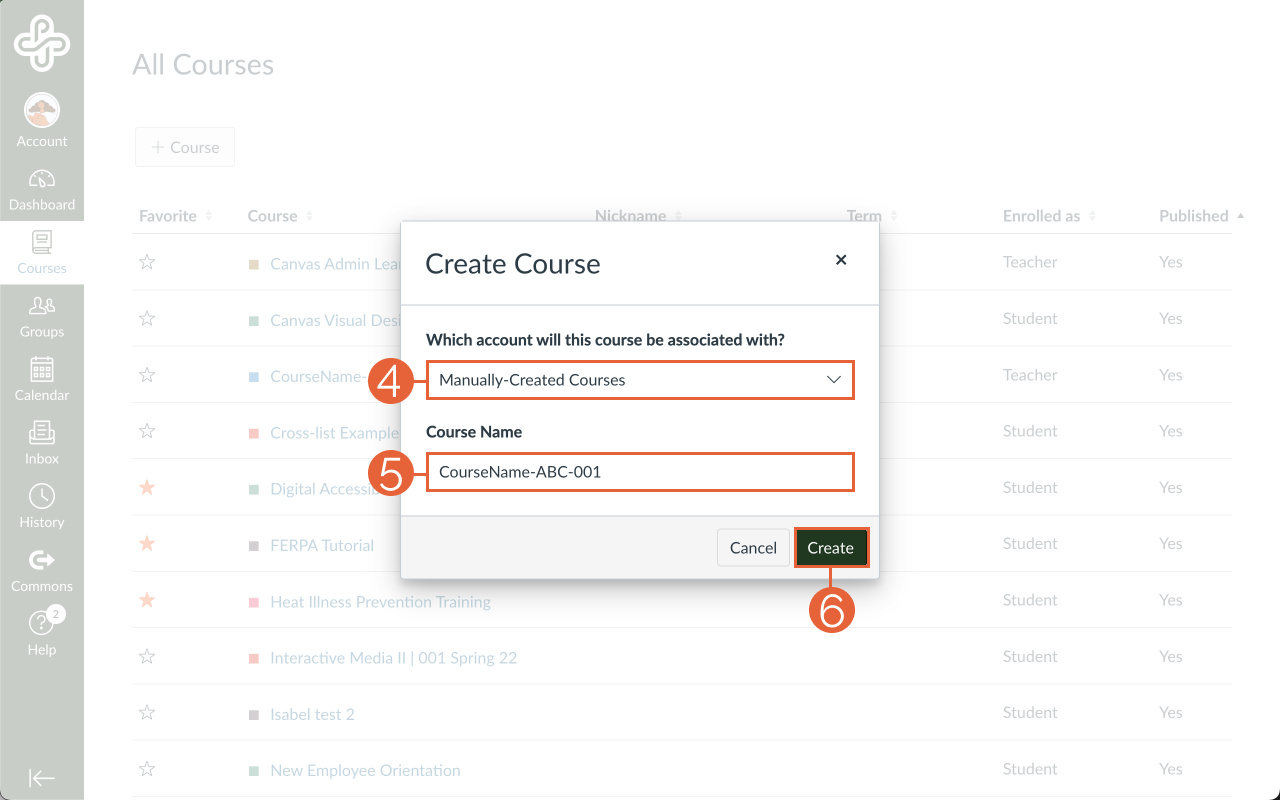

From All Courses

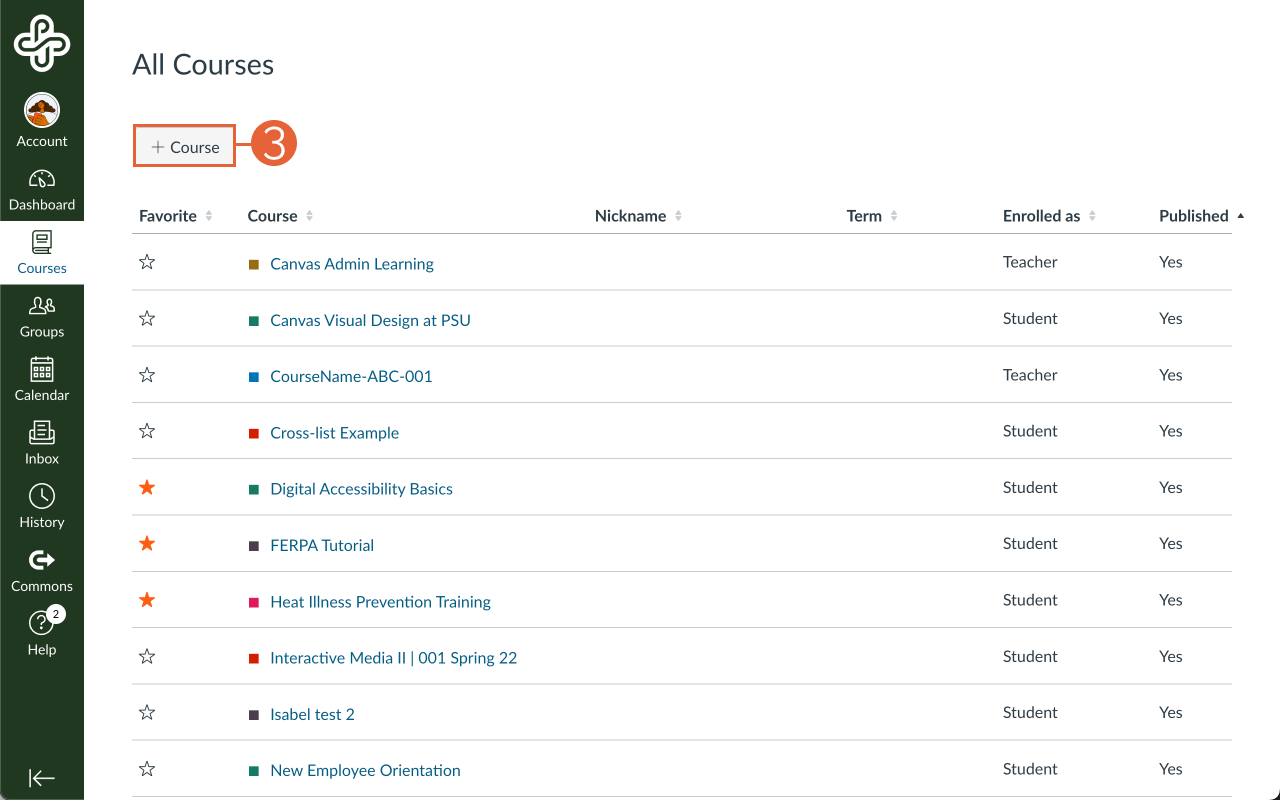

- From your Canvas Dashboard, select Courses (1) in the global navigation menu on the left, then select All Courses (2).

- Select the + Course (3) button on the left-hand side of the page.

- Select Manually-Created Courses (4) from the “Which account will this course be associated with?” dropdown menu.

- Enter a name for your new course in the "Course Name" (5) field.

- Select the Create (6) button at the bottom of the page.

New to Teaching Online

New to Teaching Online

Resource type: Self-paced Canvas course

Intended for: New faculty, emerging practitioners

Contributors:Aifang Gordon, Misty Hamideh, Lindsay Murphy, Scott Robison

This asynchronous course is designed to provide you with essential skills, tools, and strategies to effectively teach online for the first time. Through flexible, self-paced modules, you will explore key topics such as student engagement and best practices for leveraging technology to create a dynamic and interactive learning experience.

The course content is organized into modules based on the time of the term. Each module’s content will focus on two key areas: community care and course care.

-

- Community care identifies ways to support the connections students make with each other, you, and course content.

- Course care highlights administrative tasks necessary to make your course run smoothly.

What does the Teaching Online at PSU course cover?

This module includes suggestions for preparing your course and connecting with students to set a positive tone for a successful new term.

- Prepare your online course, including copying over materials and completing a Canvas course checklist.

- Recognize the importance of building a community with your students through early communication, accommodating individual student needs, and offering Zoom office hours.

- Address last-minute logistics.

This module includes strategies for establishing instructor presence and laying the foundation to maintain engagement and community throughout the term.

- Create a communication plan to introduce yourself and the course to students.

- Implement icebreaker activities to foster student interaction and build community.

- Develop strategies for ongoing engagement with students.

This module includes suggestions for maintaining a strong instructor presence and fostering a supportive learning environment.

- Plan optional midterm review sessions and provide summary feedback to reinforce key concepts.

- Maintain engagement through timely announcements, grading, and consistent presence in discussions.

- Gather student input with a midterm feedback survey and adjust support strategies.

This module offers strategies for key midterm actions to sustain an engaged learning community.

- Maintain engagement by posting announcements, participating in discussions, and sharing relevant articles or news.

- Provide summary feedback on assignments and review midterm feedback survey data to inform adjustments.

- Prioritize midterm grading and ensure your course is prepared for the remainder of the term.

This module offers suggestions for maintaining your learning community through the second half of the term.

- Send reminders about office hours and availability as students approach the final weeks of the term.

- Organize and announce optional study or review sessions to support student success.

- Motivate students with encouragement and offer a final “push” to help them complete the course.

This module suggests ways to support students through the last couple of weeks of the term and set yourself up for a successful course conclusion.

- Make sure you’re ready for your final projects and exams.

- Have a plan for late work and any extra credit.

- Verify gradebook setup and accuracy.

- Stay in touch with your students.

This module offers steps to conclude your course successfully and prepare for the next term.

- Show appreciation to students, highlight their achievements, and share your insights on their work.

- Submit final grades, approve incompletes, and reflect on feedback to plan for future course improvements.

Zoom AI Companion

Contributors: Emmett Crass, Isabel Elizalde, Eleanor Hart, Megan McFarland

Zoom AI features are disabled by default. As a host of a meeting, you can choose to enable some or all of these features.

Overview of the Zoom AI Features

When hosting a meeting, all faculty, staff, and students have access to enable a suite of Zoom AI tools that can enhance teaching and classroom management:

-

- Zoom AI Companion: During live meetings, participants can use this in-meeting chat to ask questions like "catch me up," see action items, and find out if their name was mentioned. These features keep everyone engaged in the discussion and make it easy to stay on task.

- Zoom AI Meeting Summary: After each meeting, you’ll receive a summarized version of the transcript, key takeaways, and action items. You can share this meeting summary with your students as a helpful resource.

- Zoom AI Smart Recordings: When you record your lectures, this feature automatically creates chapters, highlights, and next steps. If you choose to share these recordings with your students, they can be excellent resources that make it easy to navigate and review key content.

How do I enable the Zoom AI features?

At PSU, Zoom AI features are disabled by default. The meeting host manages these features, which are found under Account Settings in Zoom.

If you choose to enable these features, we encourage you to join our Zoom AI Companion User Group to provide feedback and share how you have integrated it into your teaching, learning, and work.

How can I use the Zoom AI companion features in my teaching?

Zoom AI offers several benefits for you to consider when designing and facilitating your course.

Zoom AI can be helpful for students with disabilities who receive formal accommodations through the Disability Resource Center (DRC). Automatic transcription, real-time captioning, and AI-generated notes can support students with a wide range of physical and cognitive disabilities, such as hearing impairments or ADHD. These features can help students with disabilities follow lectures and discussions independently, which can reduce the need for human note-takers or other more formal accommodations.

Using Zoom AI ensures students rely on institutionally approved tools rather than third-party services, such as Otter.ai. This helps protect student data and keeps your course compliant with university policies and data privacy standards, such as FERPA (Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act).

Because Zoom is widely used at PSU for hybrid, online, and in-person classes, Zoom AI fits right into a familiar environment. This eliminates the need for students to learn to use new platforms and reduces friction by keeping all course tools in one place.

With automatic meeting summaries, searchable transcripts, and AI-generated highlights, students can review material more effectively. This leads to better retention and understanding and can be particularly useful for those who need to revisit complex content.

Using Zoom AI could reduce the need for costly third-party tools. Because PSU already has an enterprise Zoom contract, extending these features to your students could be more cost-effective and eliminate the financial burden of subscribing to paid tools.

The Zoom AI Companion supports a range of learning styles—visual, auditory, and textual. With features like voice-to-text transcription and keyword summaries, students can adapt the tool to their individual needs.

What should I consider when using Zoom AI features?

The following are potential risks and mitigation strategies when considering using Zoom AI in your course design.

Students may rely too heavily on AI-generated transcripts and summaries, which could reduce engagement during live lectures. There’s a risk that students might rely solely on AI-generated summaries and transcripts without engaging deeply with the content.

Mitigation

Encourage students to use the AI companion to supplement their notes instead of using them as a replacement.

Students may misuse the AI features to seek answers during Zoom meetings, which could compromise academic integrity.

Mitigation

Zoom AI only summarizes content shared during the meeting; it will not disclose information tied to previous meeting summaries or the Internet. If needed, you can disable the AI summary for specific portions of your lecture or discussion.

While Zoom’s AI technology can provide real-time transcription and captions, it is not foolproof. Zoom AI might misinterpret complex terminology, accents, or fast-paced conversations, which could lead to inaccuracies that negatively impact the learning process. This is particularly critical in course content delivery where precise language and concepts are essential for understanding.

Mitigation

We recommend setting your account settings to share the meeting summary only with the meeting host by default, edit the summary for accuracy post-meeting, and then share it with students when it is ready.

While AI tools can support note-taking and study aids, they might unintentionally reduce human interaction in the classroom. This could affect the dynamics between instructors and students, leading to less active discussion, clarification of doubts, or engagement with human support services like tutors.

Mitigation

Consider including active learning activities encouraging student interaction, such as knowledge checks, think-pair-share, or exit tickets.

We encourage you to consider using AI tools to enhance learning and accessibility rather than to replace human interaction entirely. This feature is not enabled by default. You can decide whether to use it in your courses.

Some students may not have reliable access to the Internet or the necessary technology to benefit from the Zoom AI Companion fully. This could inadvertently widen the digital divide and put students from low-income backgrounds or regions with limited technology infrastructure at a disadvantage.

Mitigation

Avoid requiring or enforcing students’ use of this technology. Make the transcript available to students after the session, but try not to single out any student possibly facing technology challenges. We recommend sharing information with your students on accessing resources provided by the PSU Library, which include laptop and technology checkout options.

AI algorithms can sometimes exhibit bias based on the data they are trained on. In academic settings, this could lead to unequal treatment in transcription quality or highlight features for students with non-standard accents or dialects, which may further marginalize certain student populations.

Mitigation

Review the transcript for accuracy, spelling, and grammar to ensure it reflects your intended audience.

As AI tools collect and process large amounts of data, there may be concerns regarding how student data is stored, used, and protected. Although Zoom complies with FERPA, introducing AI tools could raise new privacy concerns or vulnerabilities, especially if sensitive student information is captured.

Mitigation

For confidential conversations, consider disabling the AI Companion and Summary during the meeting. Additionally, you might want to share the summary only with the host by default. This will ensure that you control when and how the data is shared.

You are encouraged to add a syllabus statement regarding the use of Zoom AI features to ensure students know that what they say may be included in a transcript summary with their name attached.

While student data is protected, we advise against engaging in conversations about student grades or anything FERPA-protected with the AI summary enabled. We also encourage you to ensure that only the host receives the AI summary for double reassurance.

Recommended Syllabus Statement for Using Zoom AI

“We will be using the Zoom AI features for virtual meetings, recordings, and transcriptions in this course. Our use of these tools is governed by FERPA, PSU’s Acceptable Use Policy, and the Student Code of Conduct. Meeting records, recordings, and transcripts will be stored securely by PSU. You may not share recordings or transcripts outside of this course without explicit instructor permission.”

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can students use this feature to record my lectures?

A: No. This feature is enabled and controlled by you as the host.

Q: Will Zoom AI own or infringe any copyright of the content I share during a Zoom meeting with this feature enabled?

A: No. Zoom AI does not claim ownership of your content. For more information, we recommend reviewing the How Zoom AI Companion features handle your data guide.

Q: Will Zoom use my audio, video, content, etc., to train its AI?

A: No. Zoom does not use your audio, video, chat, screen sharing, attachments, or other communications-like customer content (such as poll results, whiteboard, and reactions) to train Zoom or its third-party artificial intelligence models.

Promoting Academic Integrity

Contributors: Megan McFarland, Ashlie Kauffman Sarsgard

Academic integrity is a cornerstone of ethical learning and scholarship. It guides students and educators in producing original work while respecting the intellectual contributions of others. But like any skill, academic integrity must be taught, practiced, and perfected. This article explores the essential principles of academic integrity, its challenges in relation to technological advances, and strategies that can help promote authentic learning.

Academic Integrity at PSU

Academic integrity refers to the ethical standards and practices that guide students and educators in producing original work and properly acknowledging the contributions of others. At its core, academic integrity is about honesty, trust, fairness, respect, and responsibility within academic settings. These core values ensure that students are learning in a way that respects intellectual property and rewards genuine effort. At PSU, the Dean of Student Life highlights the importance of integrity in academic work and explains that plagiarism, cheating, and other forms of dishonesty are not only violations of university policy but also a detriment to the learning process. PSU provides students with several definitions of misconduct along with examples of plagiarism, such as copying another student’s work or failing to properly cite sources.

Like any learned skill, academic honesty must be taught, practiced, and reinforced. At PSU, students are introduced to the importance of academic honesty through faculty guidance and resources, especially in writing-intensive courses. Both the English Department and the Writing Center emphasize the importance of citation, research integrity, and viewing writing as an iterative process. The Writing Center offers one-on-one consultations, workshops, and online resources to help students perfect these skills. For example, writing tutors can help students understand proper citation practices, such as how to paraphrase and use quotation marks effectively when directly quoting sources. Students also have access to asynchronous resources, such as tutorials on various citation styles, strategies for avoiding plagiarism, and guidance on the writing process from brainstorming to revision. The goal is to help students think of writing as a process of entering academic conversations where crediting sources is essential.

Cultural Perspectives on Plagiarism and Academic Integrity

The concept of academic integrity can vary widely across cultures, leading to different expectations and practices in academic environments. In some cultures, memorizing information or using common knowledge without citation is seen as a sign of mastery, whereas in the U.S., failing to cite sources is often regarded as plagiarism. For students from diverse backgrounds, these differences can create confusion when navigating academic expectations. PSU faculty can play a crucial role in helping students understand that citing sources is like giving credit to other contributors in a broader scholarly conversation. This practice can be compared to actions on social media, where linking or tagging others’ content shows respect and recognition of their contributions. Framing academic integrity in this way—where citing sources reflects a respect for others’ voices—can help students see the value in these practices.

What causes academic dishonesty?

Research tells us that academic dishonesty is often rooted in a lack of skill, time, resources, and confidence rather than ill will. Common causes of academic dishonesty include time pressure, lack of preparation, and personal stress, especially for students managing high academic workloads, jobs, or families. Systemic trauma and instability, such as the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, amplify these pressures, which leads to an increase in misconduct. In these kinds of situations, students often feel that cheating is the only way to maintain their academic standing.

Research overwhelmingly shows that students with higher levels of outside stress are more likely to engage in misconduct, particularly when academic tasks feel overwhelming or unclear. Time pressure, a major concern for students balancing coursework, jobs, and other personal commitments, often leads to poor decision-making. When students feel overwhelmed by deadlines or unclear expectations, they might resort to shortcuts like plagiarism or unauthorized collaboration. Additionally, students who lack confidence in their abilities or fear failure may turn to academic misconduct to maintain competitive standing or meet familial expectations. Factors like inadequate preparation in academic research, unfamiliarity with proper citation practices, and believing that peers are also engaging in misconduct can further drive dishonest behavior. Addressing these stressors through skill building, course design, communication, relationship building, and access to resources can help students meet academic standards without resorting to dishonesty.

How do we promote academic integrity and prevent academic dishonesty?

Encouraging and fostering academic integrity often requires a multi-pronged approach. Common strategies include the use of technology platforms (like originality checkers and proctoring software) and inclusive pedagogical approaches that cultivate genuine belonging, motivation, and engagement. We explore a range of these techniques below.

Technology-Based Approaches

Originality and plagiarism checkers—such as Turnitin and Google Assignments Originality Reports—are tools commonly used to ensure that students’ work is original and uses standardized academic conventions to incorporate and cite research. The main benefit of these tools is deterring students from submitting work that is not their own.

Concerns about using these tools include valid questions about student privacy, the bias inherent in for-profit companies who wield strong influences over pedagogy and student experience in higher education, and misinterpretations of results that can lead to students being falsely accused of plagiarism.

Another concern is the longevity of these tools when higher education budgets are being cut and frequent technological developments and mergers can affect the availability of such tools. Originality and plagiarism checkers therefore require faculty to carefully consider benefits, drawbacks, risks, and uses.

Best Practices for Use

Originality checkers are best used as an option to assist students with writing drafts instead of with final assignments. During the drafting process, students can submit work through an originality checker to assess how well they have summarized or paraphrased their resources or to determine if they have left out necessary citations. They can view the common phrases that an originality checker might identify as plagiarism (because of the frequency with which these appear in other sources) and consider how to make their word choices and sentence structures more unique. Incorporating a drafting process in a writing assignment can ultimately assist not only with scaffolding assignments and time management for students but also with an active self-assessment process that improves their work and deters academic dishonesty.

To protect student privacy when using an originality checker, do not ask students to submit personal reflections or any work that contains personal information beyond their names. This is especially important if the work is stored in a repository.

To summarize, best practices for use include:

- Allow students unlimited attempts to use the originality checker software to improve their writing and citation skills

- Offer multiple assignment submissions where students can select whether or not to use originality checkers to support their writing

- Advise students against submitting drafts to repositories to avoid self-plagiarism

Make originality checker use on assignment submissions non-graded and unlimited throughout the term - Offer originality checkers as a resource for ungraded parts of the writing process (e.g. first drafts) instead of for final and/or graded versions of the assignment

- Reserve originality checker use for papers requiring citations instead of for personal reflections or other writing that contains individually-identifying information

- Be transparent about expectations for original work and how you are using these kinds of checkers

For more information on how Turnitin can be used at PSU, check out: Turnitin at Portland State University | OAI+.

In an industry response to concerns around academic integrity and generative AI use, a multitude of AI detection tools are now readily available. These tools claim to be able to detect AI writing versus student-generated writing, although their accuracy varies considerably. While many tools claim high accuracy rates in identifying AI-generated content, it is not uncommon for third-party evaluations to reveal a significant rate of false positives. As such, even detectors with strong records in identifying AI-generated content may mislabel human-authored text as AI-generated. False positives carry the risk of significantly eroding student trust and motivation. Perhaps most alarming, early research and anecdotal evidence indicates that false positives are more likely to occur among students who are English Language Learners or students with cognitive, developmental, or psychiatric disabilities.

We encourage faculty to consult with their respective departments or schools to determine if there are any required AI syllabus statements or specific guidelines applicable to their discipline. Any and all generative AI approaches should be aligned with PSU’s Academic Misconduct Policy.

As an alternative to the physical monitoring which takes place during in-person exam proctoring, exam proctoring software allows student behavior to be monitored virtually. The use of exam proctoring software is driven by a variety of factors: large courses, a large teaching load, exam reuse from term to term, barriers to closely monitoring student completion of exams, lack of grading time, etc. For faculty, this software can create a sense of security, especially for online exams.

Both students and faculty, however, have voiced concerns about using this type of proctoring software. The main concern is student privacy. Among other functions, the software records students and their environments. This can feel invasive to students and erode trust. Additionally, the software records physical behaviors such as eye and head movements in order to hypothesize the likelihood that a student engaged in academic dishonesty. While this may appear helpful on the surface, these metrics can unfairly punish disabled students whose bodies often work differently than the software expects (e.g. looking around frequently). Though students with disabilities can go through the formal ADA accommodation request process to circumvent this, studies show that the majority of disabled students cannot and do not access this nor are they mandated to if they choose not to.

Finally, it’s worth noting that even in the most ideal circumstances, exam proctoring software is not foolproof. A variety of products exist that can “trick” this kind of software and render its accuracy even less reliable.

Alternatives for Use

Besides the tools described above, what other tech strategies are possible? When using Canvas for tests, exams, and quizzes, there are several methods of adapting the Canvas Quiz settings to assist with ensuring integrity. While it is advisable to be transparent about whatever settings are enabled on a quiz, test, or exam, faculty can:

- Use Item Banks (New Quizzes) or Question Banks (Classic Quizzes): These allow faculty to pull from a repository of questions to provide students with tests and quizzes that are different from one another.

- Restrict students via Canvas Quiz settings from seeing correct (or even incorrect) answers after they complete an exam.

- Shuffle or randomize quiz questions so each student answers the questions in a different order.

- Allow students two attempts to answer every question with correct and incorrect feedback provided.

Looking for other ways Canvas can support authentic learning in your large class? Check out Best Practices for Large Courses in Canvas.

Pedagogy-Based Approaches

A key strategy for fostering academic integrity is scaffolding assignments, which helps students break down complex tasks into smaller, more manageable steps. By integrating elements such as outlines, drafts, peer reviews, and final submissions, scaffolding reduces the pressure associated with high-stakes assignments, thus discouraging academic misconduct. Low-stakes assessments are another critical tool because they allow students to practice skills and concepts without the pressure of a major grade. These assessments—non-graded quizzes, reflections, and exit tickets, for example—help students build competency over time and promote a learning environment focused on growth instead of performance. Offering diverse assessment types, such as presentations, projects, and group work, further reduces opportunities for academic dishonesty because students are evaluated in a variety of ways that require original thinking.

Active learning and student-centered pedagogies, such as flipped classrooms, are also highly effective in promoting academic integrity. Flipped classrooms, where students engage with course material outside of class and spend in-class time applying that knowledge through discussion and activities, encourage a deeper understanding of course content and reduce reliance on traditional exams. Active learning approaches, which include case studies, group work, and problem-solving activities, engage students in critical thinking and collaborative learning, which minimize the risk of cheating. By focusing on application instead of rote memorization, these methods make it more difficult for students to engage in dishonest practices.

Project-based learning (PBL) fosters academic integrity by linking assessments to real-world applications and outcomes, thus motivating students to engage authentically with the material. PBL assignments often require collaboration, critical thinking, and creative problem-solving, reducing the opportunity and temptation to cheat. Furthermore, incorporating meta-teaching strategies where students are guided to reflect on their learning processes enhances self-awareness and personal accountability in their academic work. This helps students understand how to apply integrity in their studies because they become more aware of their personal goals and responsibilities when it comes to learning.

Alternative assessments, such as ungrading and labor-based grading, promote a focus on the learning process rather than final results. These methods emphasize feedback and reflection, which reduces performance anxiety and fosters deeper engagement with the material. In ungrading, students receive qualitative feedback instead of traditional letter grades. This helps shift the emphasis from achieving a particular grade to improving understanding and skills. Labor-based grading, which assesses students based on the effort and time they invest in their work, also fosters integrity by valuing persistence and growth over final outcomes. Reflection assignments also encourage students to engage in metacognitive thinking that helps them internalize the importance of ethical behavior in their academic journeys.

Clear and detailed assignment sheets, rubrics, and expectations can play a significant role in reducing academic misconduct. PSU’s Writing Center emphasizes that providing transparent guidelines helps students understand what is required and reduces ambiguity, which can lead to unintentional misconduct. Additionally, using low-effort cheating reduction methods, such as randomizing quiz questions or incorporating peer reviews, helps discourage dishonesty without requiring significant changes to course design. Combining these approaches ensures that students are supported and encouraged to engage ethically with their work.

Establishing a sense of safety in the classroom is crucial for fostering academic integrity. When students feel secure—both emotionally and intellectually—they are more likely to engage in honest academic practices. Faculty can create a safe learning environment by fostering an inclusive and supportive atmosphere that encourages students to take intellectual risks without fear of judgment or retribution. Trauma-informed teaching practices are particularly important, because they emphasize flexibility, understanding, and empathy—all of which help create an environment where students feel safe to ask for help instead of resorting to dishonest behaviors when they struggle academically.

Equity and inclusion practices are also central to creating a classroom where all students feel respected and valued, which in turn supports academic integrity. When students perceive that their identities and experiences are acknowledged and respected, they are more likely to engage meaningfully with their coursework. Faculty can incorporate equity practices, such as diversifying course content to reflect multiple perspectives and using inclusive language, to make the classroom a place where all students feel they belong. By creating an authentic sense of belonging, faculty reduce the likelihood that students will feel alienated or pressured to use plagiarism to foster that sense of belonging instead.

Fostering intrinsic motivation is another key factor in promoting academic integrity. Intrinsically motivated students are driven by their own desire to learn rather than by external pressures like grades or competition. Faculty can cultivate this type of motivation by designing courses that highlight the relevance of the material to students’ personal and professional lives. When students see the value in what they are learning, they are more likely to engage deeply with the material. Incorporating student-centered strategies that create space for a wide variety of cognitive and physical needs—such as Universal Design for Learning—can enhance intrinsic motivation by giving students more ownership over the learning process.

Engaging students through active learning strategies is also essential for promoting academic integrity. Techniques like collaborative projects, discussions, and problem-solving activities not only deepen students’ understanding but also create a sense of responsibility to their peers. This collaborative accountability can deter dishonest behavior as students feel their actions can impact the learning experiences of others.

Promoting academic integrity requires a multifaceted approach that includes clear communication, inclusive teaching practices, and effective use of technology. By fostering a supportive environment and cultivating intrinsic motivation, educators can help students navigate academic challenges with authentic engagement and ensure that integrity remains at the heart of the educational experience.

Turnitin at Portland State University

RECENT UPDATE: The standalone site for Turnitin is currently disabled. All Turnitin assignments must be facilitated through Canvas.

Contributors:Emmett Crass, Isabel Elizalde, Misty Hamideh

Turnitin is a software designed to verify the originality of student submissions in academic settings. Integrated into Canvas, Turnitin can be used to compare student submissions to an extensive database of academic papers, web pages, and other student work to identify content similarities. This tool supports educators in ensuring the authenticity of student work and assists students in understanding the importance of originality and proper citation practices in their academic papers.

Why Use Turnitin?

Turnitin is integrated with the Canvas Assignment tool, so it is quick and easy to enable it for use with your new or pre-existing assignments. Although Turnitin is typically thought of as a plagiarism detection tool, it can often be unreliable. Turnitin may mistakenly identify common phrases and properly cited work as plagiarism. Instead of relying on the tool solely to detect plagiarism, consider utilizing Turnitin as a tool to help improve your students’ writing. It can be used to:

-

- Educate students on proper citation and references

- Create scaffolded assessments for the research paper development process

- Provide authentic inline feedback on students’ writing

Things to Consider When Using Turnitin

- The standalone site for Turnitin is currently disabled. All Turnitin assignments must be facilitated through Canvas.

- Turnitin’s AI detection feature is currently disabled. Please review Generative AI for Teaching for information on AI detection software limitations.

- Student submissions WILL NOT be used to train Turnitin’s Large Language Mode (LLM), and the tool has been thoroughly vetted for security and student data protections as recommended by OIT.

- Turnitin is optional and can be used on an assignment-by-assignment basis.

- We have two options available for using Turnitin in Canvas:

- The Plagiarism Framework allows instructors to display a similarity score within the Canvas SpeedGrader and Gradebook.

- The LTI (found under the External Tools submission type) requires users to navigate to a separate window to access Turnitin’s full grading and feedback features.

- Please review the LTI vs. Plagiarism Framework guide to determine which feature is best for you.

How Do I Use Turnitin in Canvas?

Consider the following when selecting a repository during assignment setup

- Institution paper repository: Student submissions are stored in a PSU-only database and are NEVER shared with outside institutions that leverage Turnitin.

- Do not store papers: Assignments will be compared against but will not be stored in any repository.

Student Use of Turnitin

If you use Turnitin for assignments, the following message will be presented to students prior to every submission in Canvas:

By checking this box, you acknowledge that:

- Your paper will be shared with Turnitin to generate a similarity report ONLY.

- Your paper may be stored for comparison against future papers submitted at Portland State University as determined by your instructor.

- Turnitin does not acquire any copyright or intellectual property on your paper contents.

- If you elect to view your similarity report after your paper is submitted, you will be prompted to accept the Turnitin End User License Agreement (EULA). We recommend reviewing this carefully and every time it is presented to you as Turnitin may make updates since the last time you agreed to it.

- The EULA agreement is between you, the individual user (not the university), and Turnitin, LLC, the company that licenses the tool to the university for integration through Canvas.

- If you choose NOT to accept the Turnitin EULA, do not attempt to view your similarity report. However, your instructor will still be able to view the report.

Please review the available resources on writing from the Writing Center at Portland State University and speak to your instructor if you have any concerns with using this tool.

For more help with submitting an assignment with Turnitin, please contact help@pdx.edu.

Syllabus Statement When Using Turnitin

If using Turnitin in your course, include the following statement in your course syllabus:

Note: Students agree that by taking this course all required papers may be subject to submission review for textual similarity for the purpose of detecting unoriginal writing, including plagiarism. All submitted papers will be included as source documents in the Turnitin.com reference database solely for the purpose of detecting unoriginal writing, including plagiarism of such papers. Use of the Turnitin.com service is subject to the Turnitin Acceptable Use posted on the Turnitin.com website.

For more information on building your syllabus and to download a syllabus template containing the Turnitin statement, view Building an Effective Syllabus and Syllabus Template.

Academic Misconduct and Turnitin

Turnitin should not be relied upon as a definitive source of truth that a student engaged in academic misconduct. Consider reviewing the Encouraging Academic Integrity through Course Design guide for more information.

Success Strategies for Graduate Teaching Assistants

Contributors: Kat Kane, Megan McFarland, Grant Scribner

The term “Graduate teaching assistant” (GTA) represents a broad range of labor performed by graduate students who typically either teach or support undergraduate courses. GTAs may teach their own courses, lead lab sessions, lead discussion sections, grade assignments, provide in-class support, or any combination of those duties. Expectations for teaching development as a GTA should account for the realities of life in graduate school, many of which are addressed in the sections below.

Learning to teach while bearing the weight of graduate school can feel overwhelming. Here, we want to make a simple argument about learning to teach: taking small, concrete steps based on experience and reflection is both possible as a GTA and will benefit both you and your students. This article acknowledges the unique role GTAs play in graduate school and offers strategies for Graduate Teaching Assistants to manage five of their most common challenges.

Please note: We use the term “GTA” in this article, but other student educators will likely find this content useful too.

Growing as a Novice Educator

Like traditional faculty, GTAs face time constraints and high-stakes deadlines along with intellectual, emotional, and financial stressors. Being in a graduate program simultaneously, however, places unique demands on a GTA’s time and resources. Because developing a teaching practice requires repeated practice over time, GTAs face a special challenge in this area. So how might a GTA develop as a novice teacher while keeping potential challenges in mind? Teaching development is a learning process that depends on a teacher’s ability to collect information, reflect, and adapt. For many novice teachers, the process begins with a brief assessment of teaching context and of yourself:

- What are your personal strengths, and what do you have to offer students?

- In your teaching context, what is within your control?

- What hopes do you have for students in the course?

- How will you try to incorporate who your students are (and who they hope to become) into your work as their teacher?

The answers to those questions will change over time, but thinking about how to answer them will lead you toward a path of development that has proved productive for teachers in many challenging contexts: reflective practice (Benedetti et al., 2023). Developing skills as a novice teacher doesn’t have to be “hard work”—it can happen with simple, common-sense moves like talking to colleagues or giving yourself a few moments to think about your teaching and to process recent experiences. A few ideas for incorporating reflective practice in manageable doses:

Collect informal student feedback

For example, something as simple as “How did that lab feel for you?” on an exit ticket can help you make informed choices before the next session.

Seek outside perspectives and dialogue

Ask a friend, colleague, or advisor for their take on a teaching question or a situation that came up in class. Chatting about questions and discussing the successes and challenges of your teaching has many benefits. Talking with others about your teaching can mitigate stress, lessen anxiety, and often leads to helpful insights. Simply asking a question is evidence of productive reflection on your part—your brain will continue working on it even after you have stopped giving the issue your full attention. Also, there’s no “extra work” like reading or writing involved!

Write short reflections after class

Write a sentence or two for yourself on a Google doc after each class. You can revisit your thoughts and reactions to the session when you aren’t feeling busy or tired. Looking back at the end of the term may also give you valuable (and heartening) information about how far you and your students traveled together.

Set and monitor short-term goals

Think of one small goal or objective before each class, then check in with yourself at the end to see if you accomplished it. Some teachers do this with their students, but your goal doesn’t have to be about their learning outcomes. It could be I will move around the room more or I will allow a longer silence before I jump in with the right answer.

Work-Life Balance

One of the main challenges facing graduate students, especially GTAs, is managing a near-endless list of tasks and expectations. Students engaged in research, teaching, scholarship, and life outside of academia are constantly balancing high expectations.

Overwork culture can impact GTAs in many different ways due to their dual roles in the university as students and educators. There can be immense pressure on college instructors to work long hours preparing for classes, engaging in research, and performing other academic work. Research also indicates that academia’s pressures fall disproportionately on BIPOC instructors, for whom “invisible labor” and mental health are especially impacted. The cognitive impacts of overwork culture are wide-ranging, including reduced performance, mental health crises, and even burnout.

GTAs looking to improve their work-life balance can practice setting and maintaining boundaries around how and when to decline extra work. They can also work on challenging their inner perfectionists, relying on their support networks, asking for help when needed, and extending grace to themselves when they make mistakes.

Prioritize human needs

Take time away from academia, get enough sleep, access PSU’s Basic Needs Hub, take breaks during work hours, and practice at least one self-kindness a day.

Establish clear priorities for work-related tasks and duties

Some tasks have higher stakes than others, and GTAs can learn how to expend energy on those that have the most impact. Knowing how to identify one’s own priorities and resource use in relation to the magnitude of a task’s outcome is a valuable skill.

Intentional screen time breaks

Take breaks from work communications and screen time.

Utilize interdependence

Seek support from peers and mentors for tips on balancing workload.

Mental Health

One of the main challenges facing graduate students, especially GTAs, is managing a near-endless list of tasks and expectations. Students engaged in research, teaching, scholarship, and life outside of academia are constantly balancing high expectations.

Overwork culture can impact GTAs in many different ways due to their dual roles in the university as students and educators. There can be immense pressure on college instructors to work long hours preparing for classes, engaging in research, and performing other academic work. Research also indicates that academia’s pressures fall disproportionately on BIPOC instructors, for whom “invisible labor” and mental health are especially impacted. The cognitive impacts of overwork culture are wide-ranging, including reduced performance, mental health crises, and even burnout.

Seek professional support

Access counseling at The Center for Student Health and Counseling (SHAC).

Know yourself and your brain

Learn to identify and manage anxiety/stress triggers. The first step to managing stress and anxiety is understanding what areas of your life cause them to increase. Try a worksheet to identify triggers, do some journaling, or talk with loved ones about what impacts your emotions. Once you’ve identified stressors, you can take steps (like boundary-setting, expressing your feelings, and self-care) to mitigate their impacts.

Nourish your body as well as your brain

Studies show that caring for your physical health has a positive impact on mental wellbeing and resilience. Many GTAs at PSU experience food insecurity, which can negatively impact cognition. Students can access the PSU food pantry located in the basement of Smith Memorial Student Union for free and as regularly as they wish. There are many resources available for finding nutrient-dense foods, cooking on a tight budget, and cost-saving grocery shopping. Also make note of PSU’s Basic Needs Hub.

Stay connected to community

If you’re unsure how to create community, check out the PSU clubs website for an extensive list of student organizations and events as well as cultural resources and support programs for students. Resources (not affiliated with PSU) for making friends in the city can be found here. Consider also joining Employee Resource Groups at PSU.

Embodied practice (mindfulness)

Practice attunement to your bodily needs, prioritize health, acknowledge when support is needed, and attempt to reduce cognitive load.

Navigating Power Dynamics

GTAs walk a fine line as graduate students and instructors: they are both mentors and mentees, experts and novices in their field. Helping students develop expertise is a core part of any graduate program, but GTAs are asked to represent that expertise as instructors in the midst of their own development as students. Developing identities as scholars and teachers while managing power dynamics in fields that remain largely unchanged even in the face of shifting demographics presents obvious problems—especially for GTAs who feel disempowered. Creating equitable relationships with mentors can include steps like setting clear expectations, checking in regularly regarding learning and teaching goals, establishing mutual respect, and maintaining a schedule for mentorship connections.

The academic profession is changing rapidly, creating a unique dynamic between GTAs, advisors, and the discipline itself. While advisors have a responsibility to offer authenticity, identity affirmation, and open conversation, there are steps graduate students themselves can take to cultivate positive, collaborative relationships:

Peer consultation

Having a supportive peer network can alleviate feelings of isolation and empower teaching assistants to navigate complex power dynamics with greater confidence and resilience. Peer consultation can look like regular group discussions, seeking advice from experienced colleagues, and participating in peer mentorship programs.

Discussing equity and power with one’s mentor

This proactive approach encourages transparency and mutual respect, and it enables teaching assistants to advocate for their needs and navigate power dynamics more effectively. These discussions can look like scheduling dedicated meetings to address these topics, using specific examples to illustrate each person’s concerns, and proposing collaborative solutions to foster a more equitable academic environment.

Establishing shared understanding

Establishing a shared understanding of key concepts ensures alignment on expectations and academic goals, which can reduce potential conflicts arising from miscommunication. Some strategies include jointly developing course syllabi, engaging in regular meetings to discuss instructional strategies, and aligning on assessment criteria and teaching goals.

Maintaining clear boundaries

Studies show that “leaving work at work” can greatly reduce burnout and increase professional performance. Maintaining clear boundaries helps GTAs assert their professional and personal limits and prevent potential overreach by their faculty advisors. This practice helps foster a respectful working relationship. Some strategies include setting and communicating specific work hours, establishing clear expectations for response times to emails, and delineating the scope of their responsibilities in written agreements.

Prioritizing engagement with external communities

Maintaining connections outside of the university allows GTAs to gain diverse perspectives and support while reducing reliance on their faculty advisor for validation and guidance. Some strategies include participating in local professional organizations, volunteering for community service projects, and attending conferences and workshops beyond their academic institution’s.

Career Readiness

Whether preparing for a career in academia or another professional field, graduate students are increasingly expected to have diverse skills beyond specialized knowledge of their fields. Hiring committees often expect research experience, publication skills, and pedagogical knowledge. GTAs, who are already juggling packed schedules, often struggle to budget time for professional development and other activities with which to bolster their CVs. Professional development, however, doesn’t have to be difficult or time consuming.

There are many smaller, more accessible steps that students can take, such as regularly updating their CVs, accessing job-support resources at PSU, and reaching out to potential mentors or employers. Those looking for more in-depth professional development can investigate micro-credentialing programs, attend professional conferences or networking events, and work to build their resume skills.

Update job search documents

Regularly check CV for updated accuracy, create a template for a cover letter, and reach out to potential references.

Connect

Reach out to network with potential mentors/employers within the community. There are often career-building events, job fairs, and other networking events held at PSU.

Access resources

Join the CTC program to build teaching skills, access the PSU career center, or seek support from advisors for professional development in your specific field.

Focus on career competencies

NACE guidelines share the following skills as important for career development: self-development, critical thinking, equity and inclusion, leadership, professionalism, teamwork, and technology literacy. Consider connecting with PSU Career Services for Students.

Di Benedetti, Matteo, Sarah Plumb, and Stephen B. M. Beck. “Effective Use of Peer Teaching and Self-Reflection for the Pedagogical Training of Graduate Teaching Assistants in Engineering.” European Journal of Engineering Education 48, no. 1 (January 2, 2023): 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2022.2054313.